RGL e-Book Cover 2019Š

RGL e-Book Cover 2019Š

A tale of a horde of venemous spiders and two men—

one brave,

the other not so brave—in a hidden treasure-room of the Mayas.

Weird Tales, February 1934, with "The Place of Hairy Death"

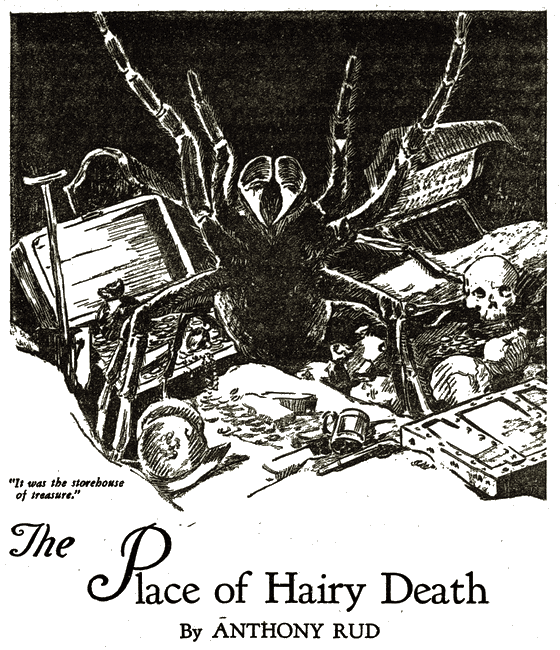

Headpiece from "Weird Tales"

AT least not alone, Seņor! If I were like you, young, handsome, and with the strength of two men in my arms, I would not venture at all down into those ancient workings. I foresee trouble; and in those horrible dripping tunnels below Croszchen Pahna, where death may lurk in every slime-lined crevice, a comrade who will not flinch is even more necessary than your own great courage.

Ah, it is not a nice place down there! I have been part way, many years ago. I suppose every young mozo in all this district of Quintana Roo once could say as much. For there was a tale of treasure, of a room of gold and skeletons. Not this cheap ore that remains, and that costs more to mine than the ore will yield. A storeroom of the heavy nuggets found in rotten rock. And sealed up with that gold, the bodies of all the Indians who worked down in the bowels of the earth for their masters, the Conquistadores.

Not the first time I ventured there, but the second, death reached out with many hairy fingers and caught its prey. The first time I descended alone, and in terror. I returned to the blessed daylight very quickly—but not alone. A multitude of hairy horrors came with me! Even now after nearly thirty years, when I eat to a fullness of carne at nightfall, I know what will happen. Ever since then, in all my dreams I see—

But the seņor shrugs. He is a hothead, like all Americanos. He wishes knowledge, not the fancies of an old man. It shall be so. Even today, the offer of fifty pesos is enough to tempt; for after all, one must eat. If the seņor will get a good comrade, and both wish it, I shall guide them halfway. That is as far as my knowledge extends. I will build a fire, then, in the Room of Many Craters, and wait. But I will not go unless I judge the seņor has a man of bravery for a comrade.

How do I know the Room of Many Craters is halfway? Well, it is a guess, Seņor, but a good guess. I believe. The Indians who slaved in the mine for their Spanish masters never saw daylight. They dwelt in this huge room, which is a great bubble in the rock.

Also, a hundred or more of them worked here in this room. The round craters were worn in the floor by many men pushing against tree trunks, and walking endlessly in circles. This ground the rotten ore, and in time scoured out the craters in the floor.

According to old story, which has much sign of truth, the gold secured from the ore had to be stored many months. Ships came seldom, not every few weeks like today when steam drives ships as legs drive water beetles, wherever they wish to go. There were no strongholds above ground; so the gold was taken a long way through a secret passage, and stored in a barren room where guards watched night and day.

And that room once was found, though its unimaginable store of yellow gold still remains untouched. Unless more slides have come, it is probable that the seņor will know the right passage or crevice, for before he may force a way it will be necessary to move a moldered skeleton.

That is not the short and rather frail bone frame of one of my people. That youth was strong, blue of eye like the seņor himself. Yellow of hair. Easy to make smile or laugh. But he did not laugh once, from the time he, his companion, and I reached the Room of Craters, where I was to wait. There is a hot, wet atmosphere down there. And among the many things that hang in that heavy air is a queer, fetid stench that sends the heart of man down into his boots.

That time, when I saw the two men leave me by my fire in the Room of Craters, I crossed myself and prayed for their safe return. I did not even think of the gold, then, though they had promised me all I could carry, as my share. The one with blue eyes, the laughing one, was such as my mother's people worshipped in the old days, you understand. I was loyal to his companion, naturally; but to him I would render any service but one! I would not go farther into that place of hairy death! No, not even loyalty could take me there. That is why I caution the seņor to choose his comrade with care.

Those two young men left me, and vanished into the wet dark. And only the wrong one returned. I must tell a little of those men and their story, so the seņor can know how that could be. Usually it is the other way. In most struggles with darkness and evil, the strongest and most right it is who comes back to tell the tale. But not this time.

The tale, the seņor must understand, is pieced together from fragments. It may not all be true exactly as I tell it. But the main facts are as I say. There is no need even to imagine a hatred or jealousy between the two men. There was none. One man was strong and poor. The other was weak—and the heir to millions of Americano gold. He, at least, should never have risked health and mind and life for more wealth. But thus it is in this world. No one is satisfied.

The blue-eyed, laughing man had been the superintendent of the great jeniquen rope factory in Valladolid, up north forty miles from here, in Yucatan. The seņor doubtless knows the factory, for he came by narrow-gage railway, and Valladolid is the terminus.

The factory, and perhaps two hundred square miles of the great jeniquen plantations, were owned by the Americano father of the second man, the dark-skinned young fellow who was known as Seņor Lester Ainslee.

It seems that the great father of Seņor Lester did not approve of his boy. It was wished that Seņor Lester get out into the jungle and what is called "rough it," drinking less wine, smoking fewer cigarettes, and learning to work hard with his hands. That was strange to me; for a sharp glance told me that one single day in the broiling sun, cutting jeniquen, would kill the delicate boy. But fathers are strange. They love and marry women who are delicate and nervous, and who die young. Then they demand their own strength in their offspring—when it is well known that Nature orders it otherwise. No breeder of fine horses would be such a fool. He would look for the characteristics of the dam to appear in the male colt; and those of the sturdy sire to show themselves in the female get.

Seņor Jim Coulter—he was the blond, laughing one—was perhaps twenty-eight, though he looked not so much older than his companion. The boy, a fortnight or so before, had got drunk to celebrate his twenty-first birthday, and there were purple saucers under his eyes remaining from that bad time.

Then it was that the rich father could endure no more. He sent the boy down from the United States to work in the rope factory, or in the fields. Alongside the most ignorant peons, you understand—mere beasts who have slaved for generations under the lash of the overseers of the haciendados!

It was asking the impossible. The factory superintendent, Seņor Jim Coulter, sent many telegraph messages; for the unreasonable father would hold him responsible, and he knew that nothing save quick death could happen to the frail young man in his charge.

In the end it was agreed that Seņor Jim would take one month of holiday from the rope factory, and accompany the boy from the north on a trip into the jungle. The Seņor Jim somewhere had got hold of a story that told of the treasure vault still remaining deep in this Madre d'Oro Mine, two thousand feet below the ancient temple at Croszchen Pahna. The story was an old one to me, of course, and probably true.

When they came to me, hearing that I had ventured down into these old workings at much risk to my life, and I assured them that no one ever had dared go far enough to find the treasure room, they nearly burst with excitement. What to them were walls that fell at a touch? What were a few deadly vipers, a thousand ten-inch scorpions waving their armored tails, or the horrible hosts of conechos—those great, leaping spiders that Americanos call tarantulas?

True, Seņor, you frown impatiently. You will say to me, ah, but everyone knows a tarantula is not deadly poison. Well, perhaps that is true. I once knew a man who was bitten in the lobe of the ear, and lived. But he had a sharp knife. And after all, part of an ear is not so much to sacrifice, when life itself is in hazard.

The conechos, Seņor, that dwell in the slimy crevices of this old Madre d'Oro Mine below the wettest cellars of Croszchen Pahna, are of a larger variety than those one finds feeding on bananas. Also they are whitish-pink in color, and sightless. They do not need the eyes. They leap surely through the dark at what they wish to bite...

The way down as far as the Room of Craters is not far, as miles are measured up here in the blessed sunshine. Perhaps there was a day when the bearded Spaniards walked safely enough from the broken shaft mouth, down the steep-slanted manways, helped here and there by rough ladders, in no more than one hour.

I know not if the way remains passable now. But if it is no worse than it was the day those two young Americanos and I descended to the Room of Craters, it will take three active, daring men more than ten times that space of time.

Roped to each other, we crawled and slid down the terrible passages. I led, and carried in my left hand a long and heavy broom of twigs bound with wire. With this I struck ahead before I placed my foot—or cleared a way of vipers and scorpions before lying down and wriggling feet foremost through narrow, low apertures where time and again my coming was the signal for a fall of wet, rotten rock.

I call to your attention, Seņor, that the way to enter such unknown passages always is feet first. Then if there are creatures waiting unseen to strike or leap at one from the side, they are apt to waste their venom on the heavy boots, or on the thighs that are wrapped in many thicknesses of paper, under the heavy trousers.

Also it is easier to withdraw, if a serious slide occurs.

Seņor Jim, who followed me, carried a strong lantern. Another, smaller one for my use in the Room of Craters was attached to his belt, near the taut rope. Seņor Lester, who came last, bore a miner s pick, for use in breaking through walled-up passages.

Once I was knocked flat and pinned down by a flake of rock like a sheet of slate, which fell before I even touched it; jarred free, no doubt, by the vibrations of our footsteps.

With the pick, however, Seņor Jim quickly released me. And while he was working there I heard him strike swiftly once, twice, thrice with the pick, though not on the rock which held me.

Then he cursed, and his voice held a note of wonderment.

"Fastest thing I ever saw!" he muttered; while behind him Seņor Lester whimpered aloud. I knew he had viewed some frightful thing, and had failed to kill it with the pick.

That was the first of the sickly-white spiders, the conechos. I had warned the two young men, of course; but until one sees those horrible, sightless, hairy monsters, and learns how they can leap and dodge—even a swift bullet, some maintain!—there can be no understanding of the terror they inspire in men.

From then on the conechos, which never appear near the surface, became more numerous. It was necessary for us to shout, and to hurl small rocks ahead of us, to drive them into their crevices. Otherwise they might leap at us. And such is the weird soundless telegraphy of such creatures, that if any living thing is bitten by a spider, all the other spiders know it instantly, and come. Whatever the living thing may be, it is buried under an avalanche of horrid albino hunger.

Long before we reached the Room of Craters, Seņor Lester—the weak one—was exhausted. He was a shivering wreck from terror, the foul air, and the heat, and was pleading with Seņor Jim to go back.

The other one would not have it. He kept mocking the dangers, laughing shortly—and how soon that brave laugh was to be stilled! But Seņor Lester got to stumbling; weeping as he staggered or crawled after us. He dropped the pick, and neither of us knew, until we reached a place where the enlargement of an opening had to be done. Then we had to retrace many weary steps to secure the tool.

At last we reached the Room of Craters, where a fire may be built from the old logs that were used by the Indian slaves in pushing the ore mill. There was comparative safety, and we rested, while Seņor Jim did all he could to revive the courage of his companion.

I could have told him it was of no use; but in those days I too was young, and did not feel it my place to advise. Seņor Lester quieted; but every minute or two his whole thin frame would be racked by a fit of shuddering. I was glad I had made it very plain I would go no farther, but would wait for them here. Seņor Jim tried every inducement, but I held firm. The few pesos I had earned outright were enough. I did not care much whether or not they found gold. The one time before I had come this far, I had penetrated a few dozen yards farther, into a narrow passage I deemed might be the one leading to the treasure room. And I knew what that passage contained—white, hairy death!

So I huddled over my fire of punk logs, ate food from the small pack I carried, slept, and waited through the weary hours. I thought hideous things, though none was worse than reality. My knowledge of what happened, you understand, Seņor, comes in great part from the ravings of a man to which I was forced to listen.

In the narrow, slide-obstructed passage that led on, those two young ones fought their way. How Seņor Jim ever made the other follow as far as he did, is not for me to guess. But struggle on they did; and at length they reached a blank ending of the passage—a place where centuries before, the Spaniards had walled in their treasure, and with it the human slaves who had dug, ground, and carried the ore and gold.

There was one small hole pierced in this wall. Quien sabe? Perhaps the prisoners broke through that much. It is likely that the dons would have a swordsman waiting outside as a guard, ready to chop off the groping arms of those dying desperate ones.

But while Seņor Lester sank on the rock floor, too spent now to help, Seņor Jim set at the wall with the pick. In time, by dint of much sweat, and many pauses in which he used the broom to brush aside the spiders, which were numerous at this low level, he had broken in a hole large enough so that a man could crawl through feet first.

He flashed the lantern into the chamber which opened beyond the wall. It was the treasure house!

His yell at sight of the piles of gold, long since burst from their hide sacks and spilled together, aroused Seņor Lester, who was able to stagger to his feet and look. They saw, besides the great mountain of gold, white traceries on the floor that might once have been the moldered human bones of the imprisoned slaves. Yes, it was the storehouse of treasure!

Frantically then, forgetting his caution that had brought him and his companion farther than any other white man, Seņor Jim wriggled into the hole he had made. He would have got through, too—only there was a slight movement of the rock, just a subsidence of perhaps six inches.

It squeezed him at the waist! It held him horizontal and helpless, two feet from the rock floor!

Seņor Lester cried out in weak terror, but Seņor Jim did not lose his head.

"You'll have to break me out—quick!" he commanded. "It's slowly squeezing the insides out of me! Quick, the pick! Hit it right up above me—there!" He nodded with his head, both arms being pinioned so that he could not point.

Whimpering, whining, almost unable to lift the pick, the other tried to obey. But that was when the first hairy thing fell or leaped from above. It landed squarely on Seņor Jim's upturned face. He screeched with horror—then with pain and realization that this was the end.

Almost before the sound had left his whitening lips, the others came, leaping, bounding, from the roof, along the walls, from the floor. The albino horde!

And from Seņor Lester fled the last vestige of manhood. Jerking back on the rope that held him to his doomed companion, he sawed at it with his knife.

When it broke he fled, screaming himself to drown the awful, smothering sounds from the end of the passage...

That is not quite all, Seņor. I heard the ghastly tale, though not until I had slept safely many hours, there in the Room of Many Craters. The young Americano had taken at least seven or eight hours to fight his way back to me. There was no hope for the other.

I brought Seņor Lester up into the blessed daylight, though because of his complete collapse we were a whole day and night on the way.

Until his father could come from the United States, I cared for the young man, who could not leave his bed. A part of his mind had gone, it seemed, and he raved about the death of his friend, saying the same things over and over. I was very glad to surrender Seņor Lester to his saddened father, who took his boy home where good doctors could care for him.

It was almost a year later when a scarecrow came to my hut. It was Seņor Lester, dressed now in rags, but with a sheaf of money with which he tried to bribe me to descend with him again into the old mine!

Valgame Dios! I would not have gone then for a million million dollars, Americano gold! The fear was too lately on me. So then he threw back his head, his voice shaking, and said:

"Then I must go alone! I can never rest till I bring up Jim's body! I—I was a coward! I am a coward!"

"Well, that is the truth," I admitted, "but there are many cowards. What difference can it make now?"

But he was resolute—in words. In actions, not so resolute. He had made up his mind to go again, this time alone; but days dragged by. He lived in my hut. He jumped each time a gamecock crowed, every time a door was closed. He was a nervous shadow, not even as strong as he had been when I saw him first. He had escaped from a sanatorium up north, and come back here secretly, I discovered. I decided to send a message to his father. When that message did go it was somewhat different from what I intended.

I was a bachelor then, Seņor. The little spiders, the malichos, spun their webs where they would on the rafters of my hut. I did not care. The mice played around freely at night; for my striped cat was old and fat, sleeping much and doing little.

To keep the young Americano from those sudden screeching fits, though, I had to climb up with a broom and wipe away the spider webs. They would build new ones. It did not matter.

"I can't stand them!" he would wail, shuddering all over. I thought to myself then there was little danger he ever would go again into the Madre d'Oro Mine. And that was true. He never went again.

That very night as I slept in my blankets on the floor, I was awakened suddenly. Seņor Lester had leapt up, screaming as I hope I never hear another man or woman scream! He jumped around. I could not quiet him. I made a light hurriedly, hearing him fall to the floor.

He was stiffening then, head arched back.

"It bit me! I killed it!" he shrieked. Then came a final shudder, and he went limp—dead!

Now that was too fast even for the bite of a great pit-viper. I tried to find what had killed him. His two hands had been clenched together, but now in death they relaxed. I drew them apart. I knew the truth, and my heart went faint within me. He had been dreaming of the hairy spiders, when—

Crushed between the palms of his thin, nervous hands, was the dead body of a small mouse!