RGL e-Book Cover©

Based on a public domain wallpaper

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

Based on a public domain wallpaper

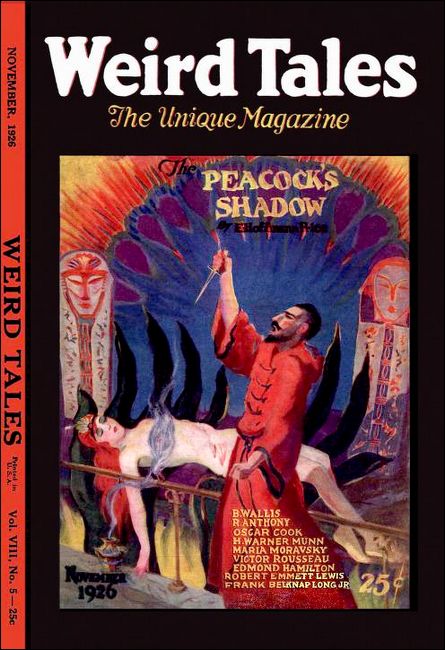

Weird Tales, November 1926, with "The Parasitic Hand"

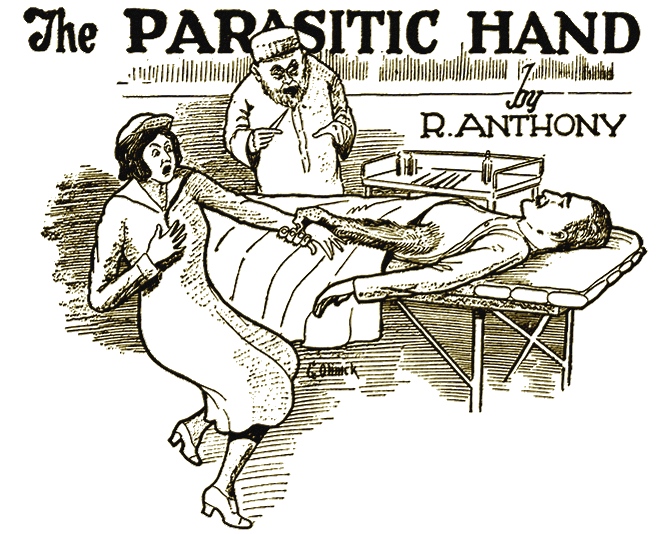

It seized the wrist of one of the nurses and held it in a relentless grip.

JUNE, 6,1925.—This morning I encountered the strangest case of my twenty years of practise. John Pendleton, a young real estate agent of Cassia City, requested a physical examination, particularly of a growth on his left side. After he had stripped I saw that he had a bandage taped to his side.

Upon removal of the bandage the growth proved to be a completely formed right hand, its base (or wrist) fastened at the curve of the eleventh rib, directly beneath the armpit. The hand was slightly open, the palm turned outward and upward. In size it was that of a babe's several months old.

"How long have you had this?" I asked Pendleton.

"Always, as far back as I can remember," he answered. "I was born with it, so I was told. But it wasn't always the same size."

I looked up in surprise. "Not the same size? What do you mean?"

He hesitated and flushed. "Well, it—it was——" He made a quick gesture and added energetically, "Doctor, don't think me a fool, or an imaginative idiot. I am a college man and not given to silly imaginings. It's the truth I am telling you, remember! That hand used to be small, very small. But in the last three months this hand has teen growing steadily. And you see its present size!"

A parasitic hand it was, clearly so. I knew the thing, for I had seen such structures before. But a growing hand! And growing after the host had reached maturity! That seemed impossible.

By accident I placed an index finger against the palm of the hand. Immediately its fingers closed upon my forefinger and gripped it firmly. Here was surprise! Usually these parasitic growths are inactive, without nerves and provided with a very scant blood supply. But the grip of this parasitic, hand was firm and strong, like that of a babe. It took considerable effort to release my finger, so tenacious was the grip.

And after I had freed myself, it continued to close and open, much like a small babe's, and finally made an infant fist.

Pendleton nodded as he observed the experiment. "That's what it does to me," he said. "But only since the last six weeks. It never did that before then. Now it's a nuisance. It clutches at everything I put on,—at my underwear, my shirt, my pajamas. The only way I can keep it from pulling and tearing at my clothes is to bandage it and tape it fast to my body. Even then I feel it wriggle and clutch at things. It's bothered me a lot. What does this thing mean, doctor?"

"Well——" I hesitated.

"Go ahead, doctor," Pendleton urged. "I've been told that it's a sort of parasite. But I don't understand exactly. How the deuce can an extra hand be a parasite? Why should a hand grow from my side? Remember, I was born with it!"

"You probably were a twin," I explained, "at least in the early stages of your embryonic life. In fact, you and the twin probably came from a single egg. Identical twins, you know, come from a single fertilized egg. Sometimes such twins are equally developed; more often one twin is better developed than the other. What it means is that the twins compete with each other during embryonic and fetal life, and one may develop at the expense of the other. As a matter of fact, one twin may absorb the other, sometimes completely so, sometimes leaving a few traces such as a hand or foot. Apparently you absorbed your twin nearly completely. This hand is all that is left of him."

"Well, I'll be hanged!" Pendleton ejaculated in wonderment. "But I clearly see how that is possible and that your explanation fits. But look here, doctor! Then in a way I must be two personalities merged in one body—myself and the other twin." He paused and his eyes grew wide with some astonishing thought. "Doctor! Do you—do you suppose that the personality, the soul, of the other twin is still intact and is now trying to establish itself in this growing hand?"

"Of course not," I said firmly.

But while I photographed him and bandaged the hand the idea suggested by his question kept revolving in my mind. I may as well put down my ideas of the matter:

If the interpretation of twins is correct, then Pendleton is the autosite and the hand is all that is left of the parasite. But what became of the personality, the soul of the parasite, when its body was merged into that of the stronger twin, the autosite? If we allow it entity, then the fact that the parasitic hand, after being dormant for twenty-three years, is now growing, would seem to indicate that the parasite was dominated by Pendleton until he had attained his full development, and that now the dormant personality of the other twin is asserting itself and trying to establish its own proper self. A strange theory! Yet it seems to fit! How else account for the growth?

JUNE 7, 1925.—I have the general photographs and the

X-rays before me. The X-rays show that the hand is completely

formed, all carpals, metacarpals and phalanges being clear and

of proper shape. A rudiment of radius and ulna are present, but

fade away near the point of attachment of the hand. The muscles

and fasciae of the hand are attached to the intercostal muscles

below the eleventh rib. Blood supply from an intercostal artery.

A doubtful spot may be a ganglion for the nerve supply.

JUNE 15, 1925.—Pendleton in again today, after a week's

absence from town. At my question, "How is the hand getting on?"

he answered shortly, "See for yourself, doctor."

He stripped, and I proceeded to remove the tape and bandages.

I started back when I saw the hand. "Why, it has grown!" I exclaimed. "It seems twice as large as last week. Like that of a child of five or six years!"

Pendleton nodded grimly. "That's why I told you to see for yourself, doctor! I wanted you to be sure about that fact. What are you going to do with it?"

"Remove it," I said firmly. "This week! It should not be a very serious matter."

A queer look came into Pendleton's eyes. "You don't suppose that in removing this—Dr—this—what is left of my twin, we would be—Dr—doing murder?"

I smiled at the fancy. "No, hardly. You may liken this hand to a tumor. Removal of a tumor does not constitute murder, does it? A tumor is a parasitic growth. This hand is a parasitic growth. We remove parasitic growths before they become too dangerous. Murder?"

"Well, no," he said. "But I had a crazy dream about it the other night," he added apologetically. "I dreamed I saw my twin and that he said, 'You have had your share of life at my expense. Now I want my own. Don't you dare tamper with things. I'm going to have my way.' And then I woke up."

"Rather obvious," I commented. "A natural sequence of our conversation of twin entities, or rather, of one twin overcoming the other. Nothing-to it, my boy." I patted him on the shoulder. "What do you say about three days from now? That will give you time to prepare. Not a serious operation, you understand. But it is good to be prepared."

He assented, and after taking a few more photographs I dismissed him.

JULY 21, 1925.—San Francisco, Calif, A telegram just

received from Pendleton: "Come back to operate. Urgent." The

illness and death of my father had called me to California before

I could operate on Pendleton. And the disposition of the estate

required a longer absence than contemplated.

I wired back, "On way in two days. Expect me by twenty-fifth."

JULY 26, 1925.—Back in Cassia City. Pendleton met me at

the station this afternoon. He looked pale and thin and haunted.

Despite the heat he was shivering. "Thank God you have come,

doctor!" he cried. "I am going insane."

I looked at him curiously. "You don't mean that the hand——"

"It's—it's growing, doctor!" His eyes held a wild and frightened look. "It is larger—and a part of the forearm has grown out!"

I stared at him in unbelief. "Hardly possible," I said.

"But it is, doctor," he insisted. "Doctor, you haven't known me for a fool. This thing has given me no rest for a month. It is always twisting and pulling, as if it were trying to reach into me for something. It's driving me mad!" Cold terror was in his voice.

The taxi stopped at my office and we hurried in. Pendleton stripped quickly and jerked off the bandages. "There!"

He was right. The hand had grown and now was the size of that of a vigorous boy of fourteen or fifteen. But, in addition, the lower half of a forearm had grown out!

JULY 27, 1925.—Removed the parasitic hand from

Pendleton's side this morning. Would not repeat the operation for

a million dollars. It was a terrifying experience.

General and local anesthetics used. But while P. responded excellently, the parasitic hand remained active; in fact, it seemed to be animated with a fighting spirit. It seized the wrist of one of the surgical nurses during the preliminaries and held it in a relentless grip, so that she fainted in horror.

Later, when I proceeded to make the first incision, it seized my wrist and with remarkable force tried to direct the scalpel toward Pendleton's heart. Only by dropping the scalpel did I avoid stabbing P. to death.

I then applied anesthetics to the hand itself, with no appreciable results. Finally, in desperation, I pushed a wad of cotton into the hand, threw a loop around its wrist and had one of the nurses hold it taut. By thus misleading and misdirecting its efforts I was able to proceed. (How silly these words sound, as if I had been dealing with a separate entity! And yet that seems to be the only plausible assumption that would help to explain).

Throughout the operation the hand kept up its writhing and clutching motions. As I made the final cut it jerked loose from my hand, fell to the floor and then fastened around the ankle of the chief surgical nurse. In horror she dropped the instruments, screaming hysterically, and ran out of the operating room and fainted in the hallway.

I darted after her and removed the fiendish hand. Even then it kept up its autonomous struggle. It was with a feeling of relief that I dropped it into a jar filled with preservative and returned to complete my work on Pendleton.

I was careful to remove all traces of the attaching structures, and also treated the vestiges with X-rays to destroy all rudiments of the growth.

The operation, though simple, and normally requiring perhaps half an hour, lasted nearly four hours, because of the constant interference of the parasitic hand. Brent, the intern in charge of the anesthesia, the three nurses and I were complete wrecks at the end of the ordeal. After we wheeled the operating table from the room and turned the patient over to the special nurse, we found that the nurses had fallen to the floor, either in a faint or exhausted.

Brent looked over the room. "Rather like a shambles today," he remarked in ghoulish humor.

I nodded and dropped into a chair, and knew no more. I believe I fainted also.

AUGUST 10, 1925.—Pendleton dismissed from the hospital

today. Only a circular scar indicates the position of the

parasitic hand.

MARCH 5, 1926.—Pendleton dropped in this morning. He looked worried and thoughtful.

"You're not sleeping well, my boy," I told him.

"You wouldn't sleep well, either, doctor, if you felt something clawing within you."

I manifested surprise. "What do you mean?"

He smiled wearily. "Exactly what I said. Something clawing and pulling within me. And right at the place where that hand was removed."

"Hm!" I muttered. "That sounds rather curious."

"Call it crazy, but I know what it is like! It is as if a hand were gripping lightly, shoving things aside, pulling at me, as if somebody—doctor, that hand is coming back!"

I looked sharply at him. No, he did not look silly. Of course, like other physicians, I knew that the imagination can produce astonishing delusions. But Pendleton did not seem to me to be of that sort.

"Strip and get up on the examining table," I ordered tersely.

With a sigh he obeyed. I could find little. The circular scar showed signs of disappearing. Below it the abdomen seemed faintly distended, but not enough to be symptomatic. The stethoscope revealed only the normal sounds, and palpation was similarly uninforming.

"Let's see what an X-ray will show," I suggested.

MARCH 6, 1926.—Just examined the X-ray prints. Nothing

important indicated, no signs of congestion as in a tumorous

growth.

I went hack through the files for the X-rays taken last June. Comparison showed that some of the internal organs had been displaced. The stomach, for one, was pushed to the right a distance of nearly two inches.

This discovery surprized me, and in my astonishment I dropped the print. I bent down to pick it up, and jerked back in amazement. For from a distance I saw what had escaped me in a closer view: a hand was outlined within the body, to the left of the stomach.

I picked up the print and examined it carefully. No, it was not a positive structure. It was merely that certain structures had been pushed aside and that the vacated portion had the outline of a hand. No evidence of actual entity, only the hand-like outline.

A puzzling case! Is Pendleton right in saying that the hand had returned? But it isn't an actual structure. A phantom, then?

MARCH 15, 1926.—Pendleton complains of internal pains

and difficulty in breathing. I have prescribed sedatives.

March 20, 1926.—Pendleton ordered to the hospital last night. Another X-ray taken, with orders to rush. Just examined the plate. The hand-shaped space has increased in size and has pushed upward. The technician called my attention to it. So she has noticed it, too! But there is no sign of a tumor. Just an absence of structures, an outline of a hand. What to do?

MARCH 22, 1926.—Pendleton suffering and in agony. "It's

reaching for my heart!" he groaned. "Can't you do something,

doctor?"

I gave him a strong sedative. After that I discussed with Brent the chances of an operation. But operate for what?

After that I went to the surgery and told the nurses of the possibility of operating on P. in a day or two. Miss Cummings, the chief surgical nurse, and her two assistants paled at the announcement, and then did something rather unethical. They refused.

"No," said Miss C., with a shiver. "No, doctor! I can't work with you on that case. I should' faint with terror."

Her two assistants expressed themselves similarly.

"Please, doctor! Don't ask me," said Miss Cummings. "I'll—I'll never forget how—how that—that thing seized my ankle." She collapsed at the recollection and began to cry softly.

"Do you wish Pendleton to die without a chance?" I asked gravely. "I must do something, I am afraid, but I do not know what to do. I do not know what is troubling him. He is suffering, that is evident. The X-rays tell too little. As it is, I must proceed on a pure guess. I do not know what I'll find. But it is Pendleton's only chance. That is, if you will do your duty."

"Duty!" The appeal to duty was effective. Miss Cummings smiled faintly and said in a low voice, "Very well, doctor! I'll try!"

Her assistants nodded in fearful assent.

MARCH 23, 1926.—The climax came this morning. I was

making the rounds of the patients and stopped in Pendleton's

room. He had slept quietly last night, he said. "Still, I feel

queer, doctor! As if things had come to a decision. Sort of ready

for the final battle. It's going for my heart, I know, trying to

take my life for its own. Can't you do something, doctor?"

I reassured him and remarked that we would probably operate on him tomorrow.

"Thank God!" lie muttered. "I don't think I can stand this much longer. Do you think you can rid me of this—whatever it is?"

"I hope so," I answered. "In fact," I added, quite contrary to my actual belief, "I feel sure that I can. I've been studying up this matter and know something definite now."

My fabulation gave him confidence and he seemed more cheerful. So I left him and went down the corridor to see other patients.

Scarcely ten minutes later I heard a fearful scream, a choking cry of "Help!"

I rushed into the hallway and saw the nurses making for Pendleton's room. But they stopped at his door and shrank back.

I ran up and pushed them aside.

Pendleton was in a turmoil, his bed a cyclone of whirling sheets and blankets. He was twisting, tumbling, and bounding up and down, his groans fearful to hear.

Just a few seconds! Then the sheets were whipped aside and I saw Pendleton. His face was red, eyes blood-shot and staring glassily, the mouth wide open, chin pendent, and tongue protruding.

"He's—he's—got me!" he gasped; his body rocked uncertainly on his lips in a rotary motion; a final "A-a-ah-h-h!" Then he snapped erect, and fell over on his side.

Pendleton was dead. I tried restoratives, but it was no use. The coroner, Dr. Bidwinkle, performed the autopsy, in which I helped him. We found the abdominal organs pushed aside as indicated in the X-rays. Just above this the diaphragm was ruptured, the lung shoved aside, the pericardium ripped open. The heart was contracted and furrowed, as if a fully grown hand had squeezed it until it stopped heating.

Dr. Bidwinkle was astounded. "Of all the crazy things!" he muttered.

So I told him of the case and also showed him the photographs. "Hell!" he exclaimed, after I had concluded. "You and I, Burnstrum, don't know it all! I think you're right, but we can't afford to expose ourselves to possible ridicule. Your X-rays and witnesses wouldn't convince one out of ten physicians. There are some people that you simply can't convince! So why bother? Here's what I propose to put down on the certificate: 'Death from hemorrhage induced by internal rupture.' Do you agree?"

"Yes, it will be better that way," I said. "But kindly note this!" I added, turning to Pendleton's body. I reached over and placed the fingers of my hand—the right hand—into the impressions or furrows of Pendleton's heart. The fingers and thumb fitted the grooves.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.