RGL e-Book Cover©

Based on a painting by Hermann Hendrich (1854-1931)

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

Based on a painting by Hermann Hendrich (1854-1931)

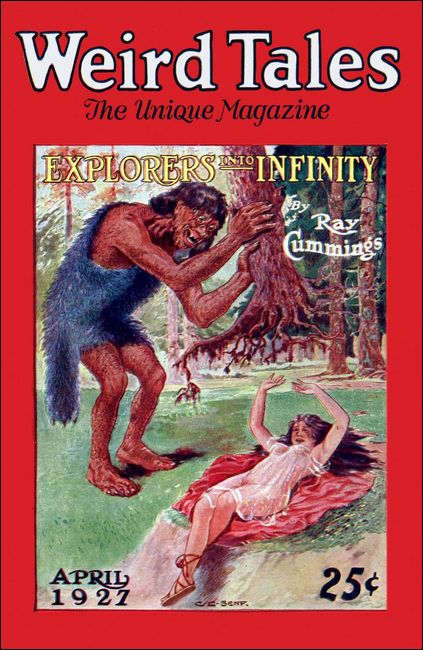

Weird Tales, April 1927, with "The Endocrine Monster"

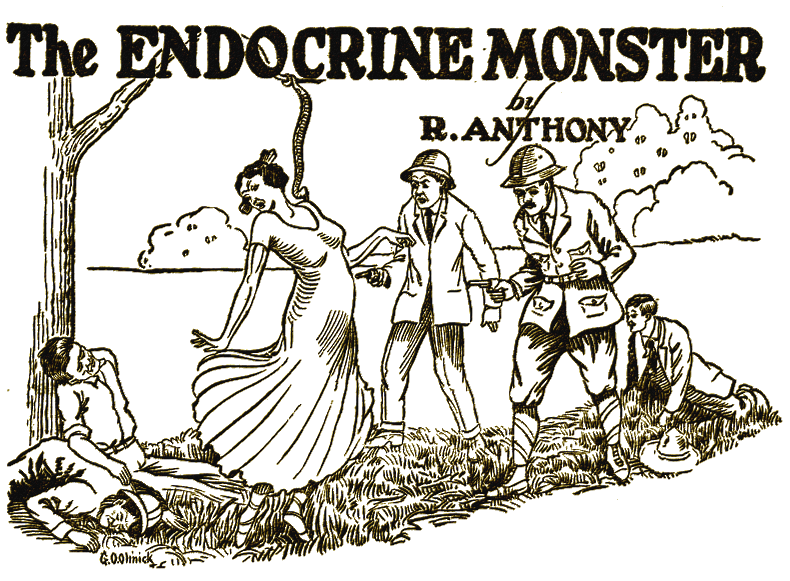

As Bonita pivoted toward us, something yellow and

shiny slithered down from above on her shoulder.

IT was my usual mid-weekly visit to Dr. Wilkie's laboratory. For some reason a large and heavily barred animal cage had arrested my attention. Its sole inhabitant was a small guinea-pig.

"What's the idea of this big cage for a dinky guinea-pig?" I demanded promptly. "Going to make a lion out of him?"

Dr. Wilkie grinned. "Perhaps," he said. "As a matter of fact, the ordinary cages are not strong enough to hold Andy. That's what I call this chap. Just watch!"

He took an empty basket cage, the square kind with half-inch meshes of chicken-wire and open at the top, and dropped it into the barred cage, covering the guinea-pig. "Now watch Andy!"

Anyone who has ever watched guinea-pigs in a laboratory will have noticed the patience of these animals, which makes them such ideal subjects for experiments. They are passive and never show signs of fight. This Andy chap, however, was different, decidedly so. As soon as the basket cage fell over him, he reared up and began to claw the chicken-wire. To my amazement the wires bent and snapped like so many feeble threads. In scarcely ten seconds a rent was made, sufficiently large to permit Andy to pass through.

But Andy was not content with the opening. He turned to another spot and ripped and tore, then to still another point to repeat the performance. He tore and twisted with a quiet ferocity that was completely startling in a guinea-pig. In a short minute the basket cage was reduced to a mass of accordioned shreds.

After that he ran to the bars and began to nuzzle them.

"Good Lord!" I exclaimed, drawing back a bit. "He's—doctor, is he bending those bars? Or is my imagination making me think they are bending?"

Dr. Wilkie waved a competent hand and remarked, "I guess they'll hold Andy all right. But let's go into the library and smoke while I tell you a story. Only"—he made an ironical grimace—"only remember this: Andy isn't a he at all. This he is a she. Andy is a female guinea-pig, not a male. At least Andy started out that way. But now——"

This is the story Dr. Wilkie told me that night.

ALL this happened rather more than twenty years ago. We were a party of seven going up the Parana on an old stern-wheeler, the property of Don Ramon, one of the seven. We were on our way to the Gran Chaco to get—— But why bother about that part? We never got there. And that's the story.

It wasn't a lucky trip. Engine trouble, snags, leaks, and what-not, and finally a terrific pampero that drove us up on an island in midstream, and partly wrecked our stern wheel. It also wrecked our only boat and marooned us on the ship, since to get to the shore we would have to wade through shallows populated with greedy jacarés and alligators.

Fortunately some huge floats came down the Parana within a few hours and the rafters stopped to help us make repairs.

And it was then that we first heard of the "Strong One" or the "Strong Demon," as it was called. We told the rafters that we were making for the Gran Chaco and that we intended to leave the ship near Villeta and pole up the Brazo Occidental into the Chaco.

"Santo Cristo!" exclaimed one of the rafters. "Stay away from there, Señores! There is something fearful there!"

"Something fearful?" Don Ramon inquired. "What do you mean?"

"We know not, Señor," the rafter replied. "But there must be some—some demon there. There, at the mouth of the Brazo Occidental is the Peninsula del Circulo where ships and rafts stop for the night. They prefer that to the harbor of San Lorenzo a mile farther down. But now they are afraid!"

"Well, tell us, then," Lassignac demanded in his peremptory way.

"The people told us. They warned us. We must stay in camp and not leave it. But Juan Felista, one of our company, heeded not. He went out into the night—to meet some woman it was—and returned not. In the morning we searched. We found him"—here he shivered and crossed himself—"Señores, his back was broken—like that-!—and his chest crushed in! And he was a very powerful man!"

Arnheimer and Connaughton, the leaders of our party, looked at each other. Arnheimer was a German who had "gone native." Connaughton was an American of certain brilliancy and uncertain passions. His particular crony was Darrell, with whom he had hunted the world and had been hunted in turn.

"Bah!" Darrell exclaimed. "A jaguar, I'll bet!"

"No, no, Señor," the rafter protested. "It could not be a jaguar. A jaguar tears with his claws. And he rips the throat with his teeth! This—this demon—he crushed! Juan Felista was crushed—as you take a reed and crush it in your hands."

Arnheimer was listening carefully. The rest of us were listening, too. But somehow I felt that Arnheimer was at home among these people and would know if they were lying, or simply imagining things. "It sounds strange," he said after a minute's thought. "A snake?—But we have no large snakes any longer. Not in these parts. Farther north, perhaps, in the deep jungles. But hardly here. What think you, Señores?" he asked the rest of us.

Mostly we shrugged our shoulders and looked wise. Janis, however, made a slight gesture to call attention and asked, "Did you see any tracks?"

The rafter nodded. "Yes, Señor, there was a streak through the grass, and some giant footprints beside it. It surely must be a demon! The blessed mother protect us!"

"Oho!" Connaughton burst forth. "Then there were tracks! I thought demons never left tracks!"

"Tracks or not," Lassignac bristled, "we shall see! We'll look for the thing! Unless the Señores feel that their well-being can not be risked!" he added with an insufferable air of patronage.

Darrell surveyed him with a cold stare. "You damned little porcupine! I'll size up your well-being in a moment!" Lassignac made a gesture which was an insult in itself. "You Americanos! Bah! You always know so much! And then you don't!"

Darrell let out a blood-curdling screech and yelled, "One more slant like that and over you'll go! Right to those damned jacarés! Just look at the pretty things clap their jaws!" And then he laughed.

Janis interfered. "Whoever is sent to the alligators, the sender follows him! I'll see to that!" His voice was chilly and they all knew that he meant what he said. Tall and thin, with a look of innate refinement, he seemed out of place in that bunch. Still, it was the sort of thing he liked. He had trained for medicine, but hated to practise, and hopped around the world in search of adventure.

Janis' words stopped the quarrel and we turned to the rafters.

"But what of San Lorenzo?" asked Don Ramon. "Do they know of the demon there?"

"Oh, yes, they know!"

"And have they seen it?"

"No, Señores! Nobody has seen the demon. They are afraid to! They would see—and then die!"

Arnheimer stroked his beard and evolved another question: "But what becomes of the tracks? Or didn't you follow them?"

The rafter shivered at the memory and grew pale. "Señores," he said hoarsely, "they stopped at the body of Juan Felista, and then—then disappeared!"

"Well, I like that!" said Connaughton with a chuckle that sounded rather ghoulish under the circumstances. "But didn't you follow to the place where they started?"

The rafters hemmed and hawed a bit and finally admitted that they had been afraid to follow the trail into the forest. And that was all we got out of them.

It was a bit unsatisfactory, but just enough to whet our appetite for more. We resolved most certainly to pay the Peninsula del Circulo a visit, and speculated on what we might find.

A few days later we docked at the village of San Lorenzo, below the mouth of the Brazo Occidental. We had to stop there to arrange for the ship and to buy flatboats to ascend the Brazo.

THERE is not much to say about the village, except that the

people looked as though they all had malaria. They were listless,

thin to emaciation, with a muddy, unhealthy color. The swamps, of

course!

During our evening meal in the single café I noticed Connaughton getting very restless. He was always restless, but now he was worse than ever, pecking away at his food, drinking a lot, and eyeing the señoritas on the square. Before the rest of us finished with our meal, he arose, stretched, gave us a smile, and murmured, "I'm off! See you later!"

Darrell called after him, "Careful, Ned! That demon, you know!"

We were surprised by Connaughton's departure. All except Darrell, who shrugged and said in explanation: "It's always that way with him. Every few weeks. If it wasn't for the women, Connie would be one of the biggest men in the States in whatever line he cared. University man and all that. Had plenty of money to start with, but——" He stopped himself as if he had said more than he intended. "Women! Huh!" he muttered.

"But, Señor Darrell!" Don Raman complained. "This Señor Connaughton—will he be back tomorrow to go up the Brazo with us?"

Darrell shook his head. "Don't know. He'll come back when he pleases. Perhaps tonight, perhaps not for a couple of weeks. Oh, don't worry about him! He'll catch up with us. Ned's always there when the divvy comes."

There was little to do that night except to loaf and talk and finally go to bed. Next day, too, we lolled around; except Arnheimer and Don Ramon, who were arranging for flat-boats and men to take us up the Brazo. Late in the afternoon Don Ramon told us he had got the boats. But we would have to do the poling ourselves, unless we eared to wait over for several days, since the morrow was some sort of church holiday. On feast days these people would not work.

"Well, a little perspiration will do us some good," Janis said reflectively. "Sweat some of this rotten alcohol out of our system and harden us for what is coming in the Gran Chaco."

Toward sunset the place began to fill up. The feast days and Sundays brought many people to the village, we were told, and, as in many other Catholic countries, celebration began the eve before the feast. The people were dressed in their best and were rather interesting. Lots of them were Spanish, Portuguese and Italian in origin, but most of them rather mixed in blood, I thought.

After our evening meal we were again seated around a table in the patio, all except Connaughton, who had not yet returned. But there were more people now, chatting, drinking, singing, and playing. Altogether it was getting lively. Occasionally there would be dances, solo or in pairs.

Somewhere near 9 o 'clock I noticed a young woman slip into the court through a small side entrance. Her movements were sinuous, reminding one of a cat, but remarkably graceful. A light mantilla was thrown over her head, so that we could not see her features. But sire was young, that was evident from her movements.

She sat down a few tables from us. With a flirt of her wrist she flung back the lace mantilla, and then we saw her face. When I tell you that I have never forgotten that face, you can imagine that it must have impressed me. To this day I see it vividly before me just as I saw it that night. Yet when I try to describe it, it evades me.

It was beautiful, there was no doubt about that, beautiful with that warmth and class of the high-bred Spanish type. To this was added something of the somber sadness of the Indian. Yet it seemed to me that there was also a certain wildness, a strange ferocity hidden there. Again, it seemed as if she were not quite a woman, since there was an incipient angularity about the jaws and forehead such as one finds in men in their late twenties and in women in their fifties.

Her figure, too, while slender and beautifully rounded, seemed somehow to have larger and more angular proportions than the delicate ones one expects to find in a girl. Her hips, for instance, were larger than necessary. Some of our athletic girls these days look that way, at times.

Even so, I am not sure that I am not permitting ensuing experiences to superimpose later impressions on that first impression. After all, I was only a lad at the time, just out of college and not yet twenty.

As she ordered her wine, her voice sounded melodious, but throaty, with a curious huskiness.

I'll admit she interested me and I could hardly keep my eyes off her. The rest felt the same way, so they told me later. In fact, almost everyone in the patio seemed to feel like that.

She drank silently, her brilliant eyes darting hither and thither. Then the music struck up, and with a sudden jerk she arose and swept into a dance in the center of the court. It was one of those rapid Castilian melodies, which later changed into a slower movement.

This girl danced with marvelous grace, doing the intricate steps with the assurance of long practise. She seemed to vibrate life. Then as the music took up the slower air, she changed. She twisted and turned, and swayed and shook. Her gestures seemed to beckon, her body seemed on fire with life.

From somewhere I caught the remark, "It is the fair Bonita."

Of course that meant nothing to me. What got me was her dancing. I had seen some pretty passionate stuff in those hot-blooded countries. But this was more than passion, it was invitation.

BONITA stopped with a final whirl. At once there was a torrent

of applause in which we joined, calls for more, and offers of

drink. Someone reached over to seize her arm. And again I was

startled. With a quick move she thrust the hand aside. But the

force of that blow was sufficient to hurl the man clear to the

wall, breaking down intervening tables and chairs.

Around us the people spoke. "Bonita is very strong. She is stronger than a man," they murmured.

Surely strange, I thought. Beyond a momentary angry flash in her eyes Bonita gave no further sign of displeasure. She smiled and nodded to the people. Then she caught sight of us—evident strangers in that village.

Her eyes widened, then grew small with sudden resolution.

She came toward us with a feline swagger, the mantilla draped over her shoulder, hands on her swaying hips, eyes flashing, and lips curled in a fascinating smile. She moved slowly, each step an alluring swagger, till she reached our table and stopped before Don Ramon.

There she fastened her eyes on him, and he seemed to be held as if hypnotized. They stared at each other, Bonita with her head tilted invitingly, Don Ramon apparently irresolute. Not a word was spoken between them. But Don Ramon began to flush a slow red; he got up, muttered an excuse to us, and left with the girl.

"So Don Ramon likes women, too," Darrell remarked cynically.

"This woman, this Bonita," said Arnheimer, "where does she come from?"

We inquired, and someone said. "She lives in a cottage on a small farm at the edge of the forest, a little way above the Peninsula del Circule, opposite the rapids of the Brazo Occidental."

"Where the demon is?" Darrell asked.

The man looked startled. "By the wounds of Christ, Señor, do not mention that! We are all of us afraid of it, of that thing, whatever it may be. All except Bonita. She has never been harmed."

"And she is not afraid?" Lassignac queried.

"Not the slightest. She laughs at our fears. But, Señor, we have seen them, the dead ones, right in that jungle near the Peninsula, at the edge of the swamps. All killed the same way! All crushed, with their ribs broken and their backs broken! Holy Mary, it was terrible!"

"But were any of them eaten?" Janis put in.

The man looked a bit surprised at this question. He pondered for a while before he answered. "No," he finally said. "The bodies were crushed and left there."

"A strange demon," Janis mused. "All animals kill either for food or in self-defense. Here apparently it is not a desire for food. Still, it is hardly conceivable that any human would attack a being so powerful that it can crush in defense."

Arnheimer nodded in agreement. "May I ask how long this has been happening? And how many have been killed?"

The man eyed the two with fearful interest. "Careful, Señores! I hope you do not intend to attack that—that—whatever it is?"

Janis smiled. "No, hardly that. But answer our questions."

"A little more than a year ago, I think, was the first time that someone was killed."

"From this village?"

"No. And that is strange, Señor. It is always people who are visitors here like yourselves."

Darrell laughed shortly. "Doesn't sound good for us, does it?"

Janis waved him to silence and asked, "How many were killed?"

"We are not sure, Señores. Two, sometimes three a month. And many we probably never found. Bonita told us of cries and shrieks and groans not far from her house. But when we went we did not always find anything."

"Humph! Did Bonita ever see this—this—demon, as you call it?"

"No, Señores." Someone just then called our informant and that was all we could learn, since others seemed to know even less.

"Well, that settles that," said Darrell. "I move we look up that thing. It's got me going."

"Very well," announced Lassignac. "I, too, will go. Or I will lead!" he said with insufferable grandiloquence. "And where a Lassignac leads others may well follow!"

"Cut out the trumpets and bass drums, you fish!" Darrell snapped. "We'll all go together and——"

Arnheimer stopped him with a gesture. "No, we can not go," he said. "Tomorrow early we must start. Don Ramon should be—should be rid of the girl by then. And perhaps Connaughton will be back, too. We can not bother with these side issues in view of the purpose of this trip."

That settled the matter for the time.

BUT Don Ramon did not come back. After breakfast next morning

we looked in his room and found his bed untouched. Nine o'clock

came and the bells in the decrepit old church began to ring for

mass, and our partner was still absent. So we decided to look for

him, whether he liked that or not.

Since we knew he had gone with Bonita, we inquired the way to her home. We could take the road, we were told, such as it was, which led past the cottage. Or there was a shorter way, if we followed a faint path along the edge of the swamps. The latter would be nearer, but was not much used on account of the mosquitoes, and the danger—from the demon.

Despite the caution, we decided to take the path, figuring that Don Ramon would hardly return quite openly along the road, but would take the concealed way.

We found the path boggy and dark, and thick with mosquitoes. Fortunately, we had head-nets with us, so we were protected at the most vital points. The jungle got thicker as we went on, hedging in on the path, until we seemed to move between two solid walls of vegetation. Later we skirted a swamp and the trees grew thinner, although the ground vegetation was a greater tangle than ever. Finally we seemed to be leaving the river, since the ground became firmer and the trees more scattered, much like some of the open "parks" in Texas.

And then we saw white water ahead.

"Hello!" exclaimed Darrell, who was in advance. "That must be the Brazo! But how the deuce——"

"Yes," said Arnheimer. "Apparently we have got onto the Peninsula-del Circulo!"

"The lair of the demon!" Darrell laughed. "Ha! We weren't going to look him up! But we're here after all!"

"We may find him," Lassignac cried excitedly, "and then——!"

Janis smiled amiably. "And then we go right on. We're here to look for Don Ramon, remember! Let's strike back along the Peninsula and see if we can't find our path again. We must have lost it somewhere, I'm sure."

So we turned away from the rapids toward the neck of the Peninsula. As we went along we saw signs of clearing, of human activity. Camping spots, of course, where the boatmen and rafters had laid over.

Darrell, once more in the lead, suddenly stopped and pointed to something in the grass. "Connaughton's cap!" he exclaimed.

We crowded around him. There lay the cap, beside the path, as if carelessly dropped. We all recognized it at once.

"He's around here somewhere," said Darrell. "Oh, Ned! Oh, Connie!" he called.

We joined him in the call, but except for the noise of birds and insects, and the chatter of some little monkeys, we heard nothing like an answer.

"I'll bet he's around here somewhere," Darrell insisted, in a curiously flat tone. "Let's look for him!"

Although he didn't say it, we knew what was on his mind. We saw his face suddenly grown pale and strained. And I feel sure that the rest of us looked no better.

"Have the demons got Connaughton?" was what he had left unsaid.

We had brought our revolvers and automatics with us. Silently we drew them and then we spread out to search.

The point where we found Connaughton's cap was at the neck of the Peninsula. So we were moving toward the main river bank. The ground vegetation there was a bad tangle and difficult to get through, but in places it would leave fair-sized spaces covered with lush grasses, looking like comfortable spots for camping. I had reached one of these grass plots, when I noticed that it looked somewhat different from the others I had examined, as if someone had sat there and kicked holes in the sod. Not recently, that is, but a day or two before. You know, in such moist places tracks do not keep long.

Well, I did my best to follow them. The tracks led through the bushes, over other grass plots. It was chiefly by the broken branches and torn leaves that I was able to follow at all. Finally I came to a thick group of trees on a small hillock. I dared not approach directly, so I moved sideways around the elevation, trying to pierce the gloom of the thicket, looking carefully up and down, prepared for every attack.

Half-way around I caught the glimpse of something gray. I stopped and watched sharply. No movement. I bent down to look along the ground. And there, in the semi-darkness, I could discern something like a body in gray linens. The humming of flies and the odor of decaying flesh apprised me that something else might be close by.

I called to the others. Meantime I looked for some sign of a wild beast, but saw and heard nothing. Seeing the others approach, I pushed forward through the bushes.

There, twisted strangely, eyes protruding and glassy, blood oozing from the distorted mouth, lay Don Ramon! He was quite dead, that was evident. And a little farther, partly hidden behind the bole of a tree, lay another body, clad in white ducks.

Even before I saw the face, I knew it would be the body of Connaughton. Flesh-flies were swarming around it in masses. He must have been dead fully twenty-four hours. In those latitudes flesh decays rapidly, you know.

"My God, it's Don Ramon!" exclaimed Darrell, the first to come up. His glance flew to where I stood. "And over there?" He came over and saw the body. "Ned!" he groaned.

He turned ghastly pale, and for a moment I thought he was going to faint. But he sank to the ground and there he sobbed, the hard, broken, tearing sobs of a man. It was agonizing to hear him.

Beside Don Ramon's body stood Lassignac, pain unutterable on his frozen features. Till then I had been inclined to despise the chap as a heartless braggadocio; now his sorrow drew me to him. Arnheimer and Janis had come up also and stood there silently, but with a look of iron resolve on their bleak faces.

They were all a strange, even piratical, crew. But it seems a human law that man must love something or other. So Darrell had loved Connaughton, and Lassignac had loved Don Ramon, and had gone with them into crimes and unholy adventures. Moralists will jeer at such affection. I did not then, nor do I now. There was a weak spot in the moral make-up of every one of them. They knew it of themselves and recognized it in others, and perhaps it was this community of weakness that had drawn them together. Like and like, as the old blurb puts it.

IT was Janis who finally roused Darrell. "Come, Jim! We have

work to do!"

Darrell shook himself and got up. "Yes, we've got to find—that—that thing!"

Janis was examining the bodies with professional sureness. "Ribs crushed, back broken in both," he said. "As if someone had embraced them!"

"But what?" barked Lassignac. "Surely no human! Don Ramon was strong as a gorilla. I've never seen him beaten."

Janis shook his head wonderingly. "I don't understand this. As we said the other day, there is no animal that simply embraces and crushes." His glance took in Arnheimer, who was moving away slowly, looking at the ground. "The tracks, of course! Let's look for them!"

"Damn it, yes!" Darrell cried and swung in beside Arnheimer.

It was clear that the latter had found something, for he was moving forward, away from the hillock. Since they were careful not to step on the tracks, I could see them myself. What I saw was a streak leading from Don Ramon's body, and beside it some oblong footprints of huge size, but spaced the length of an average person's step. In the dank, lush grass they were quite clear.

They led through the undergrowth, between trees, until we reached an open space, where they mingled with a lot of miscellaneous tracks. There the grass had been pounded down, as at a picnic. And with this we saw other evidence.

"That's blood!" Darrell exclaimed. "That's blood, or I'm a fool! Here's where the thing got Connie and Don Ramon, and then dragged them to that hillock!"

Arnheimer nodded. "Quite true! They evidently fought here. See how the grass is stamped into the ground. But there is a confusion of tracks here. We might circle the spot and see if we can find any other tracks like those going to the hillock."

We adopted the suggestion, some of us going one way, the rest in the other direction. At a point opposite our starting place we met.

Nothing! We were puzzled, and somewhat frightened. What was this thing that could leave huge footprints and still vanish in thin air? I did a little perspiring right then and there and shed not a few ripples of goose-flesh, let me tell you.

It was Janis again who found the solution. "Humph!" he said. "If this were Africa I'd say it was a gorilla or some such apelike creature. But this is South America, and as far as I know there are no large apes here. That eliminates that. Of course, there is a possibility of a huge ape, but it is not probable. Let's take the probabilities first, before we bother with the improbabilities. Darrell, you and Lassignac circled the other way. Did you see any other tracks besides those giant footprints we were looking for?"

"I? No!—Oh, wait a minute!" Darrell looked perplexed for a moment, then turned quickly and retraced his steps. "Over here!" he called back. "Over here!"

We ran after him. There were tracks there, not at all like those we were seeking, but as if some human had run lightly through the grass. The grass was nearly upright, but the marks were still discernible.

"That's what I mean," said Janis. "Let's take the normal probabilities. Whoever ran here is certainly human, and may know something of what happened here. Further, since these tracks look fairly recent—certainly not older than the thing's footprints—then this human must have seen, and must be made to tell! And note that the tracks go only one way—away from the spot, and also away from the hillock with—the bodies! That human must have made tracks in coming here. And since none are visible they must be so old that they are wiped out, just as those of Don Ramon, who certainly came to this point last night, are wiped out. Hence this person must have been with Don Ramon at the time. Suspicious? Indeed, yes!"

There was no need to urge us onward. In a few minutes the new tracks led us to the outskirts of a small farm, where they vanished near a hut at the edge of the forest. The hut was hardly more than a hovel, just four walls of mud mixed with straw, and a small lean-to.

No sound came from the hut. With youthful impulse I moved forward, ahead of the others, and sneaked up to a small window. From within came the regular breathing of some sleeper. I peered into the gloom. On a bed of straw, covered with a light blanket, lay some person—a woman, I thought.

I reported back at once. It was decided to wake her and question her.

"Better be careful," said Lassignac. "There may be more than one there."

His voice had a peculiarly penetrating quality and he spoke louder than he had intended. For at once there was some stirring in the hut, and a few seconds later the door opened and there stood—Bonita!

"I'll be damned!" said Darrell in disgust. For some reason we had forgotten about her, although we knew that she had gone with Don Ramon the night before. But we were looking for something monstrous and hideous and grotesque, for in our minds only that sort of thing could be associated with the fiendish killing of our friends and others. Yet here was the brilliant dancing girl of yesterday, and the tracks led straight to her door! I was befuddled, completely so.

"Let me question her," said Janis. Without waiting for a consenting reply, he addressed her. "Señorita, where is Don Ramon?"

With her streaming hair, and dressed in a sack-like garment, she looked the Indian part of her rather than the Spanish. I mentioned to you, didn't I, that she was of mixed blood? She didn't appear to be the least bit embarrassed or afraid. In fact, she faced us with a certain reckless confidence, such as one sees in boxers when they are sure of having an easy time with an opponent.

Janis repeated the question. She smiled and shook her head. "Señores, I know not where he is," she said.

"But you must know," Janis insisted softly. "Why did you run away from him during the night? Out there in the forest."

This time she did not smile, but looked at Janis with sharp eyes. "I ran away," she said slowly, "I ran away because—because that—that thing came. I heard it—and then ran."

Janis eyed her contemplatively. "This—this thing, as you call it—has it ever attacked you?"

"Oh no, señor. It kills only—men!" And here she laughed rather gleefully. It gave me the shivers.

"If that is true, if it attacks only men, then why did you run away from Don Ramon and leave him?"

This time Janis had scored. Now I saw the purpose of his questions. Bonita saw it, too. But she snapped her fingers. "Oh, là là! I just heard—and ran."

"You—you ran—you, who are very strong? When your strength added to Don Ramon's might have saved him?" Janis continued with emphasis. His eyes gleamed with sudden light. "Yes, and Connaughton, too!" he added sternly.

Bonita became enraged at Janis' insistence. "What care I for these men?" she flared. "I could kill them myself! I could kill you!" She stamped the ground in anger. "And I will! I will!" she screamed.

Darrell came running from behind the hut. We had not seen him disappear, he had moved so quietly. But now he came in a rush, waving something at us.

"I've got them! She's the murderer!" he called, pointing at Bonita. "You—you she-devil!" he bellowed at her. "Though you're only a woman, blast you, you're going to die! And die right now!" He flung the things he carried into Bonita's face.

As they fell to the ground we saw what they were. Just large, oblong strips of leather fastened to a pair of ordinary woman's shoes—that's all. But at once we understood how the tracks in the forest could be made with them. Most certainly well, this footgear had made those extraordinary footprints.

"You—you demon! You monster!" Darrell continued furiously. "You killed Connaughton and dragged him away! You killed Don Ramon and dragged him away! I don't know how you did it! But I know that you are going to die for it! Get ready, you!"

Darrell swung up his automatic.

"Good God!" I muttered. I couldn't understand at all. Was Darrell really going to shoot this woman? What had she done? Left Connaughton and Don Ramon to be killed, so I thought. Certainly he couldn't mean that he believed she did the killing herself!

I moved toward Darrell to stop him and tried to call him. But I never said what I wanted to say.

IT happened like a flash. Bonita whirled to one side and

Darrell's gun roared. He missed her. With a tigerish spring she

was on him.

And then I saw what I never would have believed had I not seen it myself. With a quick blow she knocked the automatic from Darrell's hand. Then she flung her arms around him. Darrell fought furiously, screaming curses. But that was only for a moment. And then I saw his face turn crimson, his eyes seemed to pop from his head, we heard a dull crash, a smothered gurgle, blood rushed from Darrell's mouth, and he was flung aside, broken, dead.

This woman, still not much more than a girl, had crushed a grown man to death!

I think none of us moved. The speed, the ghastly horror of it, had us paralyzed.

But Bonita swung around with fury in her eyes. I was close, for I had jumped to intercept Darrell's shooting. And she seized me. I wanted to tear away, but I was helpless, my own boasted strength like that of a babe against hers. She grabbed me by the arm, pulled me toward herself and embraced me.

I felt an agony of shock tingling to my forehead and fingertips, a surging protest, a revolting horror at the inhuman thing that was happening to me. Then everything went black and I knew nothing more.

Apparently I was out only a few minutes. As I awoke I felt numb and helpless. With some difficulty I rolled over and tried to rise. It was painful. Something in my side ached furiously, stabbing me as I moved—a broken rib, as we found later.

Janis and Arnheimer were standing near me, while farther away Lassignac was busy winding ropes around an inert body. That body was Bonita, unconscious or dead.

"What—what has happened?" I wheezed.

Janis turned around. "Oh, you are alive? Thank God! I feared she had gotten you, after all!"

"Feel half alive," I said. "All right otherwise. Only weak in the back and ribs. But what's happened to Bonita?"

"Janis threw her," Arnheimer answered. "Struck her in the neck or back of the head."

"No," Janis corrected. "I thumbed her on the vagus nerve. The pneumogastric, you know. A little Jap trick I learned over in Kyoto. You may have heard of it. I wasn't sure I could shoot quick enough or straight enough to prevent her from crushing you, so I thumbed her and made her faint. Lassignac is tying her up with all the ropes he can find. Hope they'll hold her. If they don't"—he paused reflectively—"well, we may have to shoot her yet!"

Lassignac was still winding ropes around Bonita until she began to look like a bandaged Egyptian mummy. Even at that, I had my doubts about the ropes. They were old and rotten, weathered from lying around outside; but perhaps if the quality of the rope was not enough, then the quantity might do.

That's what Lassignac seemed to think. He was winding away with fervor, muttering and cursing under his breath.

I got up slowly and went over to gaze at Bonita. Just then she woke up. Recollection came swiftly to her. "What are you doing?" she demanded of Lassignac.

I could see that the latter was furious with her and with himself. The former because his friend Don Ramon was dead, the last because he was doing something that went against the grain, against the innate chivalry of his nation, and he hated himself for it. Under such circumstances a man is likely to go farther than he intends. So Lassignac.

"I am binding you," he snarled. "I will see you hanged, you female brute! You fiend, you arch-murderess!" he screamed. "Bah! Cochon!" And then he kicked her.

It was a beastly rotten thing to do. But as I said, under a strain a man may do things he would normally think impossible.

Bonita seemed to shiver for a moment. Then—it happened so quickly that I couldn't quite follow—she just seemed to bound from the ground, the ropes falling from her like so many broken threads. In the same upward motion she seized Lassignac and before we could prevent she hurled him with terrific force against a tree, where he crashed and lay inert.

She turned to the rest of us. Our guns had come up at once, I can tell you. No, we didn't shoot. At that I am not so sure that our bullets could have stopped her unless they tore her to pieces. That uncanny concentrated energy and demoniac strength needed more than bullets to stop.

But our bullets were not necessary.

She had thrown Lassignac with such force that the impact had shaken the tree. And there was something up there that was disturbed, and didn't like to be disturbed. As Bonita pivoted toward us, something like a rope, yellow and shiny, slithered down from above to her shoulder, hung there for a fraction of a second, and dropped to the ground. From there it moved through the grass toward the jungle, not smoothly, but in a series of leaps and bounds much as a coiled bed-spring bounces when you throw it, and finally disappeared in the thickets.

None of us had seen it clearly, but we all knew what it was from the way it moved. It was that deadliest of South American snakes, the fer de lance, swiftest and most venomous of reptiles.

"I'm glad it didn't come this way," Arnheimer murmured, pale to his eyes.

Bonita had scarcely moved since the snake struck her. Already her eyes were filled with horror and fear. And scarcely half a minute later she began to writhe in the first paroxysm of pain. No, we could do nothing for her. She had been struck in the neck, close to the jugular vein, a direct path to the heart. She twisted and screamed in her agony. It was gruesome, and I almost felt sorry for her.

It didn't last long. Just a few minutes. Brrr! I shudder at the recollection. The discovery of the bodies of Connaughton and Don Ramon was terrible to us, and terrible, too, was the sight of Darrell's death. But most terrible is the memory of the woman, Bonita, rippling and heaving under the action of the poison.

"Well, it's over, thank God!" said Janis finally. He had tried to ease her last moments, but there was little he could do. "But merciful God! What havoc! Bonita dead! Three of our bunch—no!"—he looked over where Lassignac lay limp against the bole—"no, four! And she'd have gotten us, too, perhaps, if it hadn't been for the fer de lance! Well, it's over!"

"Yes," said Arnheimer, his voice soft and uncertain. "It's over. Our whole expedition is over. Don Ramon and Connaughton held the key to the plans. And they are dead!"

"Well, then it's ended," said Janis. "Except to bury our friends and this—this—afflicted woman!"

"WELL?" I questioned as Dr. Wilkie finished. "What's the answer? What does it——?"

"Wait a moment," he interrupted. "Before you ask questions let me show you a passage from a recent book."

He went over to one of the shelves, withdrew a book, and marked one of the pages. "This book deals with the endocrines or internal secretions, of which you doubtless know. Before showing you this passage let me explain just one point. The adrenal or suprarenal gland lies just above the kidney, and anatomically has two parts, an outer cortex or shell, and an inner medulla or pulp. The medulla gives off adrenalin, which regulates blood pressure in all parts of the body through action on the blood vessels. The cortex gives off an unknown secretion which seems to have a remarkable influence. When it is diseased, certain curious things happen. Now read what I have indicated."

He placed the volume before me. And this is what I read:

"The main course of cortical disease proceeds as follows:

"A. In early cases there is precocious sexuality, adiposity in the pelvic region, remarkable muscular strength, recalling the enfants hercules of the French writers. In girls, there is a marked tendency toward maleness. Later on the fatty tissue is lost, the children grow thin and die of exhaustion.

"B. In young women the disease develops with phenomenal muscular strength and endurance, assertiveness and even pugnacity of behavior, and excessive sexuality; this stage is followed by the appearance of male characters, such as beardedness, general hairiness, and hair on chest and abdomen. Here we are reminded of the 'strong women' and 'bearded ladies' of the circuses and side-shows. Later the muscular strength is replaced by excessive weakness, and finally death from exhaustion ensues."

Thus far I read. "Jove!" I exclaimed. "Then this woman—this Bonita—was——?"

"Precisely," said Dr. Wilkie. "She was suffering from cortical disease. The symptoms are clear. She was really helpless, driven inexorably by a malady over which she had no control. Like the Nuremberg maiden, she crushed those that she embraced."

"Humph!" I mused. "And so your guinea-pig——?"

"Yes, I have experimented with it, causing an excessive or altered secretion by the use of certain injections. The symptoms are the same—heavy buttocks, phenomenal strength, pugnacity, even the appearance of male characters. The last I figure to be the turning point. This animal should before very long grow weak and die from exhaustion. Looking back at the experience with Bonita I feel that she had reached her turning point also, and would have died in typical exhaustion. This experiment has helped me understand her case, the case of Bonita."

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.