RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

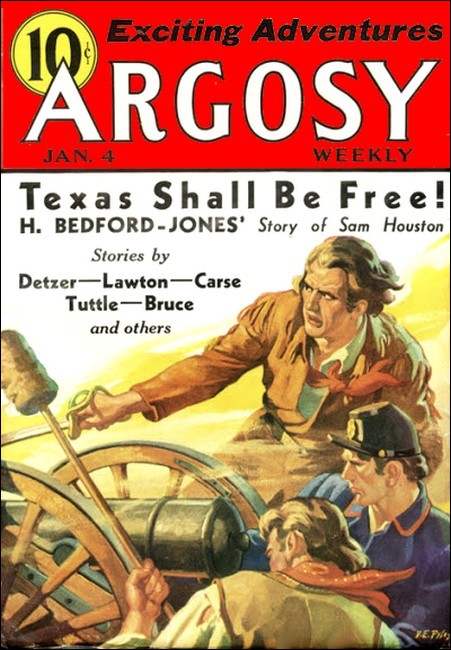

Argosy Weekly, 4 January 1936, with "The Spotted Ethiopian"

All they had to do was to wait!

Bug-Eye the giraffe wanted to be the leader of his herd, but

first he had to undergo the gravest danger known to his kind.

CENTURIES before the Chicago packing industry became modern and efficient, utilizing all of the hog but his squeal, wild, black tribesmen of Abyssinia and Somaliland were doing practically the same thing—to the ancestors of Bug-Eye the giraffe.

Bug-Eye, who stood eighteen feet tall at four years of age and was still growing, was not given to introspection. Had he been able to mull over the reason why he and his herd kept always to the open, low forest, or the still more open plateau, traveling swiftly and far at the first hint of alarm, he could have inventoried that immensely valuable commodity, himself, in the following terms:

1. Approximately sixty-five square feet of tough hide which makes highly prized' and durable leather.

2. About 450 pounds of bone and meat. Fully fifty pounds of the meat is tender, delicate in flavor. In fact, it is considered the most tasty game in all Africa. Every scrap of bone is saved and exported to England, where it is made into buttons.

3. The tendons of the long legs, and the sinews of the still longer neck, are used by all Arabia for sewing thread which will never break, and also for the strings of all the weird musical instruments which moan and whine and plunk from Port Said to the Gulf of Aden.

4. Every scrap of entrails and waste is saved for lion bait. A lion can no more turn away from giraffe liver-and-lights than a house tabby can resist the lure of a catnip ball.

Wariness was born in Bug-Eye; and Nature gave him

extraordinary advantages in the appliances of caution. In the

first place he could see from two to four times as far as either

of his two principal enemies—the lion and man. His height,

of course.

Then, those eyes! They were big, moist and mournful; not grouchy like those of a racing camel, but pleading and sentimental. From the first he could bug them outward at will, until, in the parlance of the street, "you could hang a derby hat on 'em!"

This gave the young giraffe fully three hundred and thirty degrees of vision without moving his head. The only part of a complete circle he could not see at all times was the thin segment directly behind his own small skull.

As soon as his long legs ceased to wobble under him Bug-Eye could make as good speed as a saddle horse. He did not realize the fact, but if something had come up to teach him a different gait he could have been the fastest creature on four legs. As it was, he ran instinctively in the fashion of his father, moving both legs on the right side at once, and both legs on the left side together. This made his pace a swift amble, when it might have been a terrific gallop.

Now at four years of age he was almost mature. His short-haired coat, a glossy orange-red mottled closely with chocolate spots, showed his perfect health. The markings imitated almost perfectly the sun-shadows of foliage; so that when Bug-Eye browsed upon the tender leaves and buds of mimosas and other low trees he was practically invisible at five hundred yards.

He was built in a queer fashion which once made men say that his fore legs were much longer than the pair in the rear. As a matter of fact a difference of less than three inches existed; but the strange slope from his neck to his rump gave that optical illusion. No one could have ridden Bug-Eye bareback.

His body was short and triangular when viewed from the side, ending in a long, black-tufted tail exceedingly useful in whisking off the pestilential seroot flies, which will swarm upon and poison to death a bob-tailed horse.

Watching him eat would have sent shivers down the back of an ant-bear! He had a mottled red and black tongue, covered with warty-looking papilla? When he was not eating this tongue was a mere 17 inches in length, about as long as from the elbow to the fingertips of a six-foot man.

BUT when he browsed and was just a trifle suspicious

concerning the edibility of certain buds arid leaves! That

shivery tongue was stretchable; it could elongate and squirm

forward out of his mouth like a thirty-inch serpent! It was

adapted for grasping, too, like the trunk of an elephant. It

reached out, grasped, and then held up for Bug-Eye's inspection

any morsel he thought somewhat doubtful!

Bug-Eye ranged with, a big herd when he was born and developed to the point of being able to run at all. The herd numbered thirty-four at this time, counting all the young and the drab-colored females. There were two bad lion scares; and one baby giraffe born when Bug-Eye was a year old broke a foreleg by stepping into the hole of a fennec, or bat-eared fox. The herd hung about there, mourning, sympathetic, uneasy; but there was nothing that could be done. The baby died and had to be abandoned.

Otherwise there were no fatalities, however, owing to the wisdom of Old Whistler, the herd leader. He was sharp with them all, ever ready to wheel and deliver twin punches with his thudding hoofs. And those hoofs could bowl over a lion.*

* Livingstone, the explorer, saw a native carrier get the brunt of such a double blow from a surprised giraffe. In Dr. Livingstone's words: "Igochi somehow got near without the giraffe seeing or scenting him. Suddenly the animal whirled, striking backward in the manner of a stallion. Igochi was lifted into the air and hurled backward several feet. When we picked him up, we found four ribs were broken."

The herd leader, Old Whistler, was not the tallest, but he was the canniest of Bug-Eye's herd. When grazing, or sleeping, he sent out four sentinels, who gave the shrill alarm at the first sign of any creature approaching. To this could be attributed the size of his herd and the long record of safety.

Then dawned the day of the massacre.

Old Whistler had led his subjects into the dwarf forest of the plateau in southern Abyssinia through which cuts the river known as Webi Shebeli. A swirling dust-storm came. This in itself was no hardship to Bug-Eye. He simply turned his tail to the wind, closed his eyes, and then kept his nostrils tightly closed most of the time by use of those extraordinary facial muscles which gave him such a capacity for queer expressions.

Of course he had to breathe; but he knew how to inhale slowly, sieving out the sand grains. The storm did not bother him or others in the herd—but it was the reason death came to so many, just the same.

Riding with the storm came a party of horsemen, black hunters who were returning empty-handed. The swirling dust took just this unfortunate moment to slide away in whirligigs to eastward—and right before the eyes of astonished blacks, as they lowered the protecting zaroubs from their faces, were dozens of the greatly desired giraffes! These creatures still had eyes and nostrils fast closed, and were probably unaware of the menace until the first tribesman let out a yell, swinging his great broadsword.

Then came snorts, whistles, and instant flight. But for many of the herd it was too late. The dozen or so of mounted blacks swung their swords, not attempting to kill any of the prey instantly, but hamstringing as many as possible, rendering them helpless to run.

Then, when the remnant of the herd had vanished, the horsemen came back, shouting gleefully from dry throats, to give quietus to the dragging animals on the ground, trying so gamely to haul themselves to safety.

FOR the hunters this was supreme luck. Each man had at

least one carcass—and that meant comparative wealth for his

family for at least a month. But when Bug-Eye and the others

reassembled a few miles away there were only seventeen survivors.

Bug-Eye himself was limping, bleeding from a deep cut across his

rump, a slash that had missed the fatal hamstringing by less than

a foot.

Old Whistler himself was missing! Now that was a different matter entirely to what it would have been with almost any other wild animal that runs in a herd. Giraffes do not fight each other to the death. There may be a little mild noggling between the young bucks in rutting season, with one butting his vestigial (and bristle-tufted) horns into another's face. But real fighting does not happen. The leadership of the herd usually goes to the eldest buck.

Bug-Eye was as tall now as Snuffer, a mangy-looking old fellow probably twelve or fourteen at least. Snuffer's spots were sun-faded, and when he had to run any distance he wheezed asthmatically. For several seasons he had been almost an outcast in the herd, unpopular with the females, but acting as a grouchy sort of lieutenant for Old Whistler. Now he assumed command.

Bug-Eye was a handsome creature, but still callow. He had arrogant notions, and now tried to disregard the leadership of Snuffer. There was, no fight. The other males and the females herding their young at their sides, simply looked away at the distant horizon, disillusioning Bug-Eye. His time might come; but right now not a single one of the herd would accept his leadership! They might despise and dislike Snuffer, but he had the savvy.

After two days of trying, and getting only the cold' shoulder, Bug-Eye was astonished by a command from Snuffer. He, Bug-Eye, was told with a snort and a wheeze to get out there a quarter-mile away and act as sentinel in the moonlight!

This was a job usually handed to the nondescripts, the spiritless ones. Bug-Eye went right on grazing, ignoring such an insult.

Ka-whamm! Two heavy hoofs struck him squarely in the side, throwing him from his feet. He landed heavily on the wounded side of his rump, and scrambled up, squealing unheroically. Giraffes are not fighters except in defense of their own lives or their young. Bug-Eye never gave a thought to disputing Snuffer further. He limped out to the sentinel post, and from that moment it never crossed his rather simple mind to dispute the commands of the moth-eaten oldster. But live and learn. Though the young giraffe did not realize the fact as yet, the insignificant, drab-colored females, with their ambling, loose-jointed progeny at their sides, were the real rulers of the giraffe herd. They decided which old fellow they would follow and obey. Young ones, pretenders, simply were left to whistle and talk to themselves.

They got over that immediately. Giraffes are such gregarious animals that when one is: left alone, and cannot find another herd to join, it sickens, stops grazing, and dies.

Bug-Eye was filled with the zest of life. The herd had diminished but his own self-esteem gradually mounted. He took pride now in the last inches of his growth, which allowed him to reach tender morsels on the trees which were out of reach even of Snuffer.

He mated again, and when his fifth year of life began there were six awkward little ones of his, following their placid mothers over the plateau. Only two males besides Snuffer and himself had survived; and both the others were considerably-smaller. Bug-Eye's time was coming; and in the end it was through a sort of desperate gallantry that he achieved the highest rank in the herd.

IT was only through great craft in stalking, plus some

luck, that a man on horseback could slay a giraffe. Some accident

similar to that dust storm usually had to help. Of course if the

native Ethiopians had hunted with modern flat-trajectory rifles,

it would have been a different story. But they did not employ

firearms much. A surprise from ambush, a quick spring and sprint,

a blow or two from the broadsword's—that, was the time-honored method, which did not succeed very often for the simple

reason that given three or four seconds in which to get under

way, any giraffe could outrun any horse.

Lions were a far graver peril. At even the coldest scent of a giraffe herd, tawny Numa's jaws would slaver. Many a lion; too, fell into pitfalls onto sharpened stakes below, simply because he lost caution. Giraffe innards as bait tempted him beyond control.

But where a herd of the living long-neckers was concerned, the lion would go for days and nights without food or water, pursuing, stalking—and probably sooner or later getting a chance to' leap and strike with his deadly forepaws.

Snuffer had led, ever westward, for months. The depleted band, slowly being rebuilt by a dozen young giraffes of varying ages, had reached the reedy shores of Queen Margherita Lake, when the first real lion disaster occurred—the first fatality in the life-time of Bug-Eye, though there had been plenty lion scares.

A lion and lioness, hunting together, had the unbelievable luck to see this tasty herd, frightened by something real or imagined, come flying straight in their direction as they lay in the thorn bush and reeds a hundred feet from the edge of the lake.

All they had to do was to wait! The wind was blowing toward the tawny pair, who flattened themselves cat-fashion, licking their chops, and waiting... waiting....

Simultaneous springs! Whistles, squeals of alarm. Thudding hoofs. And here and there> striking with that back-breaking downstroke, flashed the great eats, biting into the neck and lifeblood of one victim, only to leave instantly as the crimson spurted to slay another frenzied victim.

Three of the young ones, terrified and running this way and that in senseless fashion, were killed outright. The Snuffer, cornered in the branches of a thicket, turned and struck vainly with his hoofs—which missed the red awfulness of the lion's jaws.

That was all for Snuffer. He went down, screaming.

Bug-Eye had started to run, found himself headed, swerved—and there saw the lioness strike down one of the young giraffes.

Wheeling, Bug-Eye let the long, slinky brute have the entire strength of his hindquarters! The hoofs went home, striking ear and bloody jaw, cracking bone....

A minute later the triumphant male lion came from his kill, smelled puzzledly at the motionless, stretched-out form of his mate there on the ground, and then turned, tail lashing. The great roar of anger and sorrow he sent up reached the fleeing giraffe band faintly, spurring them to swifter flight.

Out there, Bug-Eye led, undisputed now. He had killed a lion.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.