RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

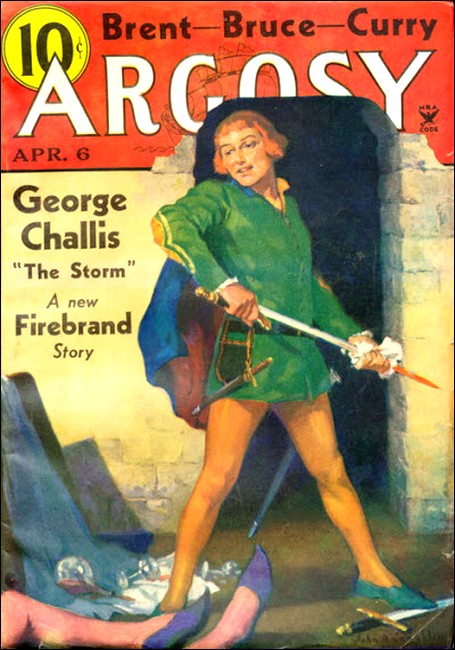

Argosy, 6 April 1935, with "The Lonely Killer"

Tube-Nose had seized the advantage in the first second of attack.

Ten thousand in a day he killed— but they were only ants,

and another jungle denizen was out to kill him.

HE has no friends, no audible sounds with which to talk to them in jungle language. He has no mate, save for one short week in the year. He has only one ambitious enemy, among all the creatures of the Orinoco valley, though millions would be safer if he died.

Of all the beasts who walk on land, man included, he slaughters in the most wholesale fashion. On any day he feels normally hungry, he can be counted upon to murder a small army of perhaps 10,000—ants!

He is the giant armored ant-bear of the jungle.

A squat, timid tapir sees him lying there on the ground, looking like some huge lump of fungus with a hairy fan on top. For a moment the horse-pig is deceived. He wonders. He lowers his curious, twitching shout.

Then up floats the stench of formic acid, the odor of ants. Three or four thousand of them, eaten for breakfast, are being crushed and digested by this creature under the hairy fan.

The tapir snorts and gallops away. Fire ants nearly ate him alive once as he slept, and he fears the scent.

The pile of fur, sixteen to eighteen inches in length and striped gray and black, suddenly rises on end! Back and up swishes slowly the most magnificent brush in the animal kingdom; a tail forty inches in length and nearly thirty in breadth, which Tube-Nose, the ant-bear, uses as a waterproof and sunproof shield for his body as he sleeps.

He lumbers up awkwardly now. A little early for tiffin, perhaps, but he can always eat. A Mundurucu Indio, hunting with his blowtube, sees him and stops. The stocky brown savage is hungry, too, but he does not raise the lethal weapon.

He watches a moment, because the great ant-bear is a rarity. He sees a beast with a body four feet long, two feet high at the shoulder; an awkward, dim-sighted animal; somewhat iike a small bear, more like a magnified polecat, but with a head and long, tapering snout shaped like a prize parsnip.

That head and mouth have no jaws at all, only the tube out of which, when he feeds, the ant-bear pokes a sticky cylindrical tongue to which ants adhere helplessly until they can be ingested. When not used, this tongue is folded double in his throat.

The body is heavily massed with gray hair, which grows more black toward the tail. There are gray streaks of hair standing up as a stiff mane along his neck and spine.

Once the Indio who watched half-raised his ten-foot zarabatan, but then he lowered it. The ant-bear had just two spots vulnerable to poisoned darts—his eyes. And when he blinks the scaled lids, it is doubtful that a dart would pierce them. Anyhow, when awake he waggles his long, parsnip head slowly from side to side, and it would be hard to hit one of his tiny, beady eyes at twenty feet with a rifle.

Over the rest of his body, under the deceptive hair, Tube-Nose is protected almost as thoroughly with plate armor as an armadillo. Snake fangs cause him no worry. Teeth and claws of the ocelot glance off and leave no marks except on the hair.

He has only one real enemy, the wisest (reputedly) of all jungle creatures; and he, Tube-Nose, is that wise creature's one incurable folly! The boa-constrictor lives long enough to acquire genuine wisdom, but he never learns how perilous it is to attempt to indulge his taste in the black, musky flesh of the tribe of Tube-Nose. Or if he does learn, he disregards experience like a dieting fat woman succumbing to a proffered cream puff.

THIS afternoon Tube-Nose saw the hesitating Indio, and stopped after two undulating, swaying-sidewise forward steps. He continued to swing his parsnip head, however, as he looked at the swarthy human creature there in his path. The black, near-sighted eyes saw enough to know that this might be an enemy. So Tube-Nose settled back to his haunches, exposing his triple-sheathed chest and abdomen, where claws of the ocelot blunted themselves instead of disembowelling, and the fiercest attacks of angry, inch-long termites were not even as much as a tickle.

Something strange and weird about him came to light then, something which went far to explain his queer waddle of a forward gait which made him look so much like some throwback to a dim age of land reptiles.

When he hunkered up for possible defence, he pulled his great talons forward out of his sleeve!

Or so it seemed. As a matter of fact he tucked them under when walking in the soft, deep leaf-mould of the jungle. They are attached to the middle toe, which has stronger muscles and tendons than the forearm of a human wrestler.

The forearms themselves are immensely strong; with them an ant-bear can hug a leopard to death. But the two scimitar claws set amid others more ordinary!

These two middle-toe claws are curved, razor-edged, heavy beveled, and from six to nine inches in length. With them—but this day Tube-Nose was going to have to show what they could do!

Not more than once a year, perhaps, was he called upon to defend himself against his one really serious enemy. So this afternoon, as soon as the Indio with the blow-tube heard a far-off squealing of peccaries, and turned swiftly to intercept this more succulent game, Tube-Nose slowly lowered himself from his haunches and went about his mission in life—which was the destruction of teeming millions of ants.

There was no expression of satisfaction on his face. In fact, if you paint a carrot or a parsnip, dead black, and stick in two black-headed pins near the thick end, you will have a miniature of the ant-bear's head at that moment. Of course the head was much bigger, and armored. More than this, it was set on a muscled, lithe neck with flexible vertebrae, so that a wallop from the paw of a big cat bothered very little.

Tube-Nose could "ride" such blows, much as a human boxer rides a punch he cannot deflect or parry. Only with much better success.

NOW he undulated along slowly through the green murk of the tropical jungle, bound for the ant towers of the Rio Capanaparo, which is a tributary of the Orinoco known to Indios and a few men of white skin—very few. Here where long ago the balata-gatherers had a camp the ground is open to the sun. And here huge colonies of black ants had swarmed to build their masonry fortresses.

Each black ant of the jungle was a fearsome creature in itself, much larger than a termite, though not as well drilled in regimental maneuvers. Seemingly each of the glistening, juicy black fellows was formed of two elongated licorice drops, held together at a waist as thin as that of a wasp. Tube-Nose fancied them, as a human gourmet fancies genuine caviar, buckshot sized. Even thinking about them in his dim way, he felt the sticky juices begin to exude from his long, deadly tongue.

The ant towers of the Capanaparo are a sight to make any man's flesh creep. Each one is built of a brown clay which bakes yellow-white in the sun. It is just about the same clay which was once used for making soap-bubble pipes, and in time it gets so hard that an ant tower four feet in diameter at. the base would withstand the direct fire of a machine gun for many minutes, and show little damage.

The towers rise from three to twelve feet in height. Each one is a systematic honeycomb of ramps and corridors and chambers, through which the black ants rush, always in a hurry about something or other. They work under orders, though, and their system of self-government is one to make human beings turn green with envy. And they fear nothing, nobody in the whole world—save Tube-Nose. Were it not for him the ants would multiply at their terrific rate, build towers faster than a sub-division builder could throw up chalk box shacks for human tenants, and soon own every leaf and stalk and carcass of animal in the whole jungle.

In fact, one noted English entomologist, Sir Henry Ripley, has predicted that in time ants may rule the entire land surface of the globe, in spite of all that Tube-Nose and his tribe can do.

Tube-Nose was not concerned with vague prognostications. His life work was appetite; and his hunger bade him attack a tower and sack it. So he lumbered unhurriedly toward one of the smaller ant-towers, containing only a few million of the juicy black tidbits.

At the base of the ant-tower—inside which no doubt there were alarums and excursions hither and thither, for the ant is a soldier and no doubt keeps sentinels posted—Tube-Nose gave a wriggle of satisfaction and sat him down. You could almost see him tie a napkin around his neck and smack his lips—only he did not have any lips, or even primitive table manners.

But then he set to work, in businesslike fashion, showing just why he had those elongated middle claws like sickles. They started in to crack the cast-iron clay of the tower. Then they dug further, bringing out chunks. And he did it in less than fifteen minutes, paying no attention until he was all set and ready for the hordes of furious black warriors who swarmed out over him, biting at his armor, trying in vain to find a spot where they could hurt him.

Ants do not know the meaning of fear; and therein lies the story of how they can be limited if never eradicated. They fight and die. Well, that was all right with Tube-Nose, who could not have eaten anything else but ants, no matter how hard he tried.

IN a quarter hour his great talons had dug a hole right into the pipe-clay tower; and this aperture swarmed with indignant tenants. Now Tube-Nose wriggled ecstatically, and settled him down to business. He poked in that parsnip snout, and the cylindrical tongue shot back and forth, almost as fast as the forked tongue of a serpent.

With it went each time a few score or hundreds of juicy ants, who were scraped off inside the throat, as the tongue licked out for more.

It was not necessary for Tube-Nose to go ahead with progressive demolition of the clay tower fortress, hunting down the last survivors in some deep-buried medieval keep. Far from it! The black ants swarmed to battle, caring nothing for previous casualties. Had Tube-Nose possessed the capacity of an elephant, he could have sat right there and filled it to repletion.

But after a time his tongue began to move with less avidity. The little black beads of eyes seemed to glaze. And finally he settled back, completely filled. The survivors in the ant tower got hurried orders from their chiefs. A long line of them went downstairs and out into the river bank. Soon they started back with loads of fresh clay, with which to repair the damage. Life must go on!

Ah yes; but that command applies equally to all creatures of the jungle. Only a few of them, like the timid but speedy tapir, are willing to subsist on leaves and grasses. The others eat each other, and would starve if they didn't. So a constant game of red murder is played under the thick green canopy of the tropical jungle.

Tube-Nose felt peaceful. In fact he never did make war on any other jungle denizen except the ant; but he had to hold himself in readiness for defense. In his time he had fought a pack of peccaries; voracious, grunting little wild pigs. He had been compelled to tear to shreds enough of them so the cannibal hunger of the rest of the pack was satisfied, before he could limp away unnoticed. He had not been injured at all, but so utterly fatigued that another hour or so of combat probably would have found him helpless.

Another time a coughing jaguar, whose mate with kittens was only a few yards distant, had tried to chase the ant-bear. Only to be hugged and ripped until it yowled and slunk away, leaving the family unprotected while it licked its hurts. But Tube-Nose had no taste for jaguar kittens, no matter what the spitting demons of parents suspected.

Now, stuffed with his favorite food, Tube-Nose wanted only a good place at the base of a tree, where he could curl up like a hedgehog on the ground, and cover himself with his great fan of tail. After such a meal he would have been good for moveless slumber until midnight—at which time he would eat again.

But as he plodded slowly on his undulating way, a queer lonely creature who cared not at all for companionship, he came under the green canopy of jungle once more. And up there on the lowest limb of a red mahogany tree was something that looked almost like a dead branch. Almost. Tube-Nose never raised his swaying snout to see, even when the dead branch rippled slowly with the constrictive hunger of the great boa....

TWENTY feet of snake. A thickness of muscle and tough skin and plated scales; the snake was as great in diameter as the thigh of a 200-pound man. An engine of destruction which could encompass any jungle denizen, circle him with those sinewed loops, and slowly but surely squeeze him out into a slender, boneless sausage fit to be swallowed whole. Any jungle denizen, that is, save Tube-Nose, where the certainty was not so great. The curious thing of it all was the fact that the boa-constrictor particularly hungered for the musk-flesh of Tube-Nose. Such ironies are not explained by Nature; they simply exist.

But when the heavy thump came, which told of the snake coils striking the soft jungle carpet, and the wide open, toothed jaws fastened to the side of his neck, Tube-Nose cast aside lethargy. Seconds now meant life or death, and he knew it.

He threw himself backward, not even waiting for the first of those ripple coils to wind about his bear-like body, and seized the mid-section of the great snake in his hugging embrace.

Instantly then his scimitar talons began to tear their way into the whiter and softer under-side of the great boa. After all, this was easy, compared to ripping a way into a flint-walled tower of ants!

It is not supposed, of course, that the boa-constrictor was just lying there meanwhile. He had come to kill and eat, and if he just once got those coils around the shoulders and forearms of the ant-bear, the struggle was finished. With his lever tail hooked in the greatest root of the mahogany tree, he swooped into a fast coil, and flung that coil like a hoop rolling on the ground, straight at his quarry.

Only that fast first act of Tube-Nose made it miss. But in a split second it was no longer a coil, but a writhing length of snake. Then it was a coil again, wrapping itself about the hind parts of the ant-bear, which were at once available and unprotected....

Then a tightening, an attempt to use leverage and make a quick kill, before this clawing, slicing fiend ripped the vitals out of the snake....

No chance! Tube-Nose had seized the advantage in the first second of attack, and not even the monstrous strength of the great constrictor serpent could make him loose his grip. Fastened to the very middle of a twenty-foot fury which tensed together in coils, and snapped outward like a released watch-spring, the ant-bear was tossed up, thrown sidewise, drubbed on the ground, constricted and then freed—and after a few seconds all the boa wanted was to get away from this leech-like thing which was tearing it in two!

Forgotten was appetite now. Viscid snake blood smeared the tree trunks and the ground. Rip! Rip! Rip! went the scimitar talons, always in the same place, almost like a woodsman's ax biting into the same V of white wood!

The great snake hissed and thrashed more wildly, hooping itself away, leaving the tree root leverage.

Then suddenly all was changed. Cut completely through in the middle, there were two snakes writhing in death throes there on the jungle carpet, leaping up and shivering, looping, flinging themselves this way and that. The end with the snake head caught a branch and went up in the tree's heights to die.

The other end flopped blindly a while till it found the edge of the water. Then something came up and seized it, bearing it below the surface.

Tube-Nose got down again to all fours. He swayed his parsnip head experimentally. Then he walked slowly away, limping a little in his right hind leg. He would seek a place where he could cover himself with his fan-like tail, and sleep off his bruises and fatigue.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.