RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

Argosy Weekly, 11 May 1935, with "First Loyalty"

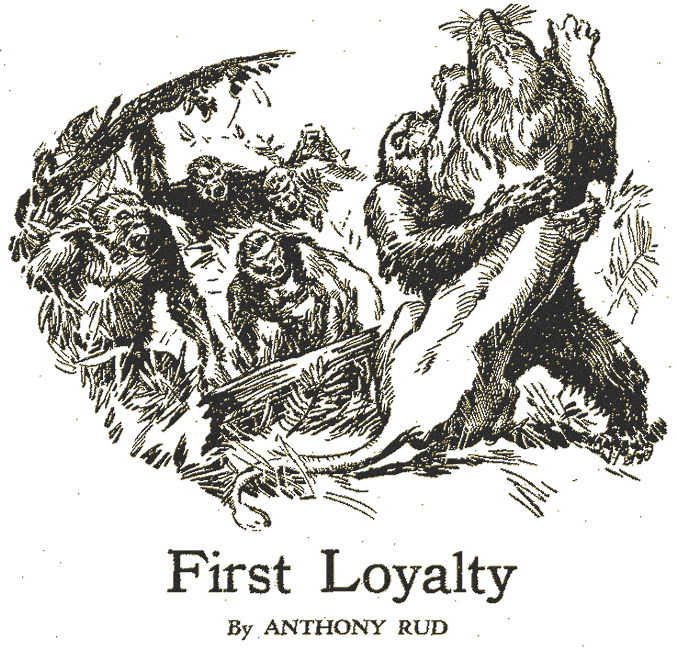

Their snarling and roaring was furious.

The terrific struggle of gorilla versus lion was no

sooner over than a more savage battle royal began.

A WHOLE dry month had passed. The Gaboon jungle had withered and turned yellow overhead, though in its murky fastnesses of green gloom and fungus growths below, little had changed. It seemed dank and changeless; but that was before the punitive expedition of white men came up the river.

A lazy black tombo had taken a large advance in trade goods for his village. Then he had forgotten his contract to furnish so and so much palm oil. The white traders could not find him, so they burned the huts of his village.

If it bad stopped there, no one would have worried much. The black chieftain least of all. It had been time to move to another location anyhow.

Fire from the thatched huts soared aloft, and crackled into a roar like that of many snare-drums, however. The great drying crown of the forest had caught! It spread, driven south and west by a wind unknown on the floor of the jungle.

Even though rains came then, the fire burned. And seven weeks later a gloomy black giant who had dwelt all his thirty-odd years of life within a dozen miles of the spot where Stanley found the explorer, Dr. Livingstone, pushed his way out of the thorn scrub and came slowly, cautiously down to the bank of a river strange to him, a Congo tributary which Belgian map-makers name the Ikatta.

He was a huge creature, this black-haired giant, even when he walked on his feet and the knuckles of his hands. In that posture he was three feet high, but so bulky and muscled of torso he could have occupied the space given to both guard and tackle in a close-line formation of human football.

The jungle was overpopulated. All sorts of animals, made homeless by the great fire, had crowded down toward water. The old man of the woods was in a grouchy temper, but cautious for the sake of the big family which followed him.

Now, just before he reached the marshy bank of the stream, a movement in the scrub caused him to stop, raising himself from the knuckles of his hands to an erect posture.

Tremendous! Though only a few inches above five feet in height, the old man gorilla was a full yard across chest and shoulders.

His long, bunch-muscled arms reached on from there, giving him a sidewise stretch of almost seven feet!

He looked uncannily like a man—but a terrible, prehistoric sort of man. This was his defensive attitude. Up on his hind legs, he was ready to batter or embrace any enemy who dared his wrath. The black lips curled away in a savage snarl, revealing the awesome, overdeveloped dog teeth. Once clutched in his arms, no animal short of an elephant had any chance to save himself from those teeth.

This was not an enemy, this new arrival who came so incautiously toward water. It was only a short-necked giraffe, that rare and beautifully-colored creature which men call the okapi—and which they have tried in vain to capture and keep in their zoological gardens.

One sight of the enormous gorilla, and the little okapi uttered a squeak of terror, digging in its tiny hoofs to the ankles, then whirling to flee.

The gorilla felt ugly. He flashed forth one arm, to catch and destroy. But his long fingers only grazed the okapi, which went from there to hide and shiver for an hour.

The snarl which accompanied that vain grab at the sunset-hued okapi, died away into growls and muttered words in ape language. A moment passed in which the old fellow gazed upstream and down. Then he turned his great head, thrusting out the heavy, prognathous lower jaw, and emitted a roar in a different key.

It was a signal to the gorilla clan. The bush became alive. Out came mothers with babies on their backs. Small children already on their own, but subject to constant discipline of the strictest sort for disobedience.

Bucks of all ages up to that of the clan leader. Young females. Gray-haired oldsters of both sexes.

Of the males, most were the sons, grandsons and great-grandsons of the old leader, though three or four had been free-lance wanderers, separated from their own clan by some mischance, and attaching themselves to this old man's protection. (After meekly submitting to a thorough drubbing at his hands and teeth!) They had mated with the younger females, who were regarded as so much rubbish by the old man.

All the apes were weary and uneasy. They hated travel, other than their ordinary feeding round of two miles a day or thereabouts. And the heavy taint of smoke, borne downwind from the jungle fire far behind, mingled with the scent of hundreds of creatures they scarcely knew by sight. Ordinary times, the gorilla finds himself alone. Other animals shun the small sector which he makes his own, though it is only in starvation times that he will eat meat of any kind.

Now the whole troop came down to the marshy bank and drank awkwardly. Two of the babies fell in, were fished out—and spanked in exactly the fashion human children are spanked. They yowled lustily. Then each forgot the pain and stopped abruptly, scurrying around to forage for berries while the elders were engaged upon building nests of boughs for the night to come.

The great leader did none of the camp-making. His work seemed done, so he hid away a few yards into the brush and sat down for a good scratch and to curry out the thorns and burrs which had caught in his shaggy hair.

Now and then he barked out gruff reminders; and females came rather sulkily, the elder ones grumbling openly. They left offerings of berries and choice strips of inner bark, which he snatched up and ate as his due. Was he not guide and protector—as well as ancestor—of the clan?

Ape children are pests. They resemble the heedless, inquisitive smaller monkeys, the fellows who hang by their tails and hurl coconuts, much more than do gorilla adults. The old ones, male and female, have a solid place in the jungle world, and dignity to protect. But urchins have no dignity; nothing but insatiable curiosity—backed by something like unthinking cruelty.

Deep in this most impenetrable thicket a spent lioness had crawled. Heavy with young, she and her mate had fled the fire, until she could go no further. Then, true to the instincts of all big cats, she had sent her lord and husband on his way. He could not assist—and she deeply distrusted his appetite, where tiny cubs would be concerned.

The male, a big buff-yellow maneless lion who looked more like a tiger than most lions do, had not gone far. Instinct kept him from traveling further along the course of their journey. The great jungle fire prevented him from doing the usual thing; returning to his accustomed stamping grounds.

He lay in covert less than a quarter-mile distant, occasionally lashing his tufted tail back and forth like a heavy whip, as the ape-sounds came to him. He did not like apes, but ordinarily he did not see or hear them. In his own domain the lion was even more of an absolute ruler than the old man gorilla in his small circle of jungle. This five-year-old male, in the prime of his strength, measured a full eleven feet from nose to root of tail. He was proud; and the only creature of land, sea or sky who could get any sort of obedience from him was his own mate. Even she had to walk in his lordly shadow, any time except when she was with cubs.

It was just then that one of the nameless ape urchins, no doubt still loved in a certain fashion by his own gorilla mother, but otherwise just an ugly little devil, crawled under and through the prickly bush—and discovered what he thought to be a dead lioness lying there.

One horrified yowl, when he discovered his mistake, and then he was knocked head over heels back into the scrub. He was badly dazed, but crawled away. The sick lioness coughed and roared and made a terrific rumpus about it. She was telling the heart of Africa that this was one time she meant to be alone!

Away there in his covert the male lion heard. Probably he thought it all out in the second his tail took to flash back and forth, for he was away in a leap. Just as though he had been lying on a great catapult which suddenly loosed. His first spring took him fifteen feet, the second one twenty; and then he went on as a yellow flash, eating up that quarter mile of distance in something like thirty seconds, despite the brush and trees and bad footing. As he came he roared encouragement.

The baby ape had recovered enough to bawl and blubber as he hippity-hopped back toward camp. He was just in time to attract the attention of the great male lion, who burst from the bush, bounded twice, then vented a coughing snarl as he batted the baby ape with his formidable paw.

This blow crushed the little one's skull, driving out all curiosity and impishness forever. But even the avenging lion forgot all about the incident in the space of a split, second. Out from the brush ambled an ungainly old man gorilla—ten times the size of the dead baby, and a thousand times more formidable!

That was all the lion saw, but there was much more. From bush and rock, each one snarling and beating his shaggy chest with his great hands, came five, eight, a dozen more male gorillas, closing in on the tawny intruder and getting in a frame of mind to tear him to fragments! Behind their men came the females, screaming rage, and egging on the men to vengeance!

The younger males, however, knew this was the business of the leader. They waited. He faced the lion, rising to his hind legs, and roaring out defiance and a promise of vengeance as he beat a tattoo on his great bass drum of a chest.

THE long yellow beast swerved, saw and charged—all in the space of time it takes a barnyard swallow to change the direction of flight.

Head hunched between his great shoulders, the gorilla stepped forward, arms extended, to seize the enemy in mid-leap!

The lion's right paw smote sidewise and down, striking with a force sufficient to slay a hartebeeste or a springbok. But this was a tougher quarry. Some hair and some blood came away in the lion's claws, but the gorilla did not even stagger or flinch. Borne backward by the sheer impetus of the lion's body, he still managed to seize the lion exactly where he had planned to seize him—around his shoulders with one great arm, over the other shoulder with the other arm.

Thus as they went to the ground, rolling over and over as roars, coughs, growls and sounds of snapping teeth and worry came from the cloud of dust and debris they raised, the old man-gorilla got his own breast and shoulders against the breast of the lion! There they were out of the way of the slashing fore-paws!

The ape, heedless of the thrashing, the rolling over and over, heedless of the great back-paws of the lion which were ripping into his own entrails, burrowed into the clinch for all the world like a human boxer in the ring, protecting his own chin by sinking it into the hollow of an opponent's shoulder.

But the gorilla was doing much more than clinch. He was straining the lion's back, almost breaking it. And beside this, the great canine teeth were biting, crunching into the yellow skin, the reddening flesh, and the spurting crimson of the lion's throat!

Such a fight of jungle titans is decided in a space of mere seconds. The destruction is too terrible to allow it to last any longer. As the ring of watching gorillas closed in tighter and tighter, the struggling figures on the ground ceased rolling. The spasmodic movements of the lion's hind legs slowed, stopped. The great puddle of red which surrounded the combatants widened. The lion quivered, what of him could be seen. The black-red gorilla had not appeared to move for some little time.

But now he pushed himself away, and fell as be tried to haul himself erect. From breastbone downward he was a visual horror, a thing which manifestly could not live. It seemed a miracle indeed that he had held on to life long enough to realize even the fact that he had emerged from this fight for his offspring, a victor!

Realize the fact he surely did, however! Pushing himself up a little on the knuckles of one hand, he beat his stained breast twice or thrice with the palm of the other, and uttered a feeble ghost of his old-time roar. Then he slumped, and lay silent, his deep-set, cruel eyes slowly glazing in death.

The females set up a screeching, a requiem which made the timid of the jungle cower for miles around.

But the males did not mourn. Even while this great combat was in progress, they had started to show their teeth to each other. Now five of the larger and more belligerent had begun a savage battle royal among themselves. The king was dead.

Who would be king?

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.